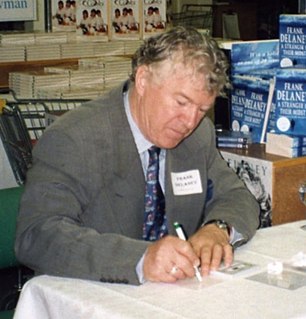

A Quote by Frank Delaney

If you need proof of how the oral relates to the written, consider that many great novelists, including Joyce and Hemingway, never submitted a piece of work without reading it aloud.

Related Quotes

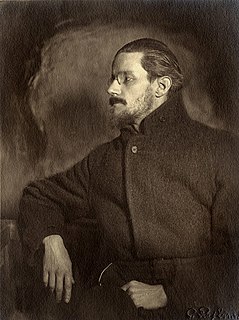

A friend came to visit James Joyce one day and found the great man sprawled across his writing desk in a posture of utter despair. James, what’s wrong?' the friend asked. 'Is it the work?' Joyce indicated assent without even raising his head to look at his friend. Of course it was the work; isn’t it always? How many words did you get today?' the friend pursued. Joyce (still in despair, still sprawled facedown on his desk): 'Seven.' Seven? But James… that’s good, at least for you.' Yes,' Joyce said, finally looking up. 'I suppose it is… but I don’t know what order they go in!

What a joy it is to read a book that shocks one into remembering just how high one's literary standards should be.... a tour de force by one of England's best novelists.... Atonement is a spectacular book; as good a novel - and more satisfying... - than anything McEwan has written....sublimely written narrative.... The Dunkirk passage is a stupendous piece of writing, a set piece that could easily stand on its own.

I've been working hard on [Ulysses] all day," said Joyce. Does that mean that you have written a great deal?" I said. Two sentences," said Joyce. I looked sideways but Joyce was not smiling. I thought of [French novelist Gustave] Flaubert. "You've been seeking the mot juste?" I said. No," said Joyce. "I have the words already. What I am seeking is the perfect order of words in the sentence.

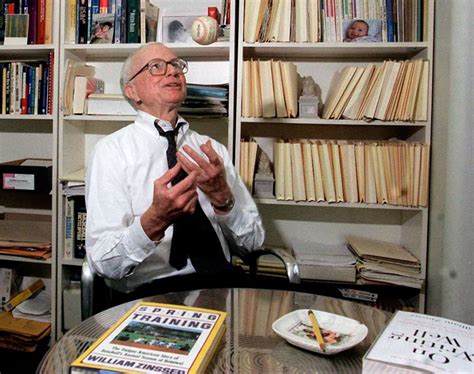

I think it's a great thing to hear the author reading. I've listened to CDs of Cheever and Updike reading their stories and Hemingway. To hear what their voices were like is amazing. Whether they're reading well or not, it's great to listen to the intonation and the beat of the guy who wrote the story.

Unlike most readers in Antiquity who read their books aloud, we have developed the convention of reading silently. This lets us read more widely but often less well, especially when what we are reading-such as the plays of Shakespeare and Holy Scripture-is a body of oral material that has been, almost but not quite accidentally, captured in a book like a fly in amber.

When I saw what painting had done in the last thirty years, what literature had done - people like Joyce and Virginia Woolf, Faulkner and Hemingway - in France we have Nathalie Sarraute - and paintings became so strongly contemporary while cinema was just following the path of theater. I have to do something which relates with my time, and in my time, we make things differently.

Mann and Joyce are very different, and yet their fiction often appeals to the same people: Harry Levin taught a famous course on Joyce, Proust, and Mann, and Joseph Campbell singled out Joyce and Mann as special favorites. To see them as offering "possibilities for living", as I do, isn't to identify any distinctive commonality. After all, many great authors would fall under that rubric.

My book, Oral History: Understanding Qualitative Research is about how researchers use this method and how to write up their oral history projects so that audiences can read them. It's important that researchers have many different tools available to study people's lives and the cultures we live in. I think oral history is a most needed and uniquely important strategy.