A Quote by Frederick Lenz

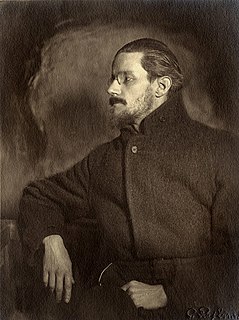

In one particular chapter in Ulysses, James Joyce imitates every major writing style that's been used by English and American writers over the last 700 years - starting with Beowulf and Chaucer and working his way up through the Renaissance, the Victorian era and on into the 20th century.

Related Quotes

To live with the work and the letters of James Joyce was an enormous privilege and a daunting education. Yes, I came to admire Joyce even more because he never ceased working, those words and the transubstantiation of words obsessed him. He was a broken man at the end of his life, unaware that Ulysses would be the number one book of the twentieth century and, for that matter, the twenty-first.

A friend came to visit James Joyce one day and found the great man sprawled across his writing desk in a posture of utter despair. James, what’s wrong?' the friend asked. 'Is it the work?' Joyce indicated assent without even raising his head to look at his friend. Of course it was the work; isn’t it always? How many words did you get today?' the friend pursued. Joyce (still in despair, still sprawled facedown on his desk): 'Seven.' Seven? But James… that’s good, at least for you.' Yes,' Joyce said, finally looking up. 'I suppose it is… but I don’t know what order they go in!

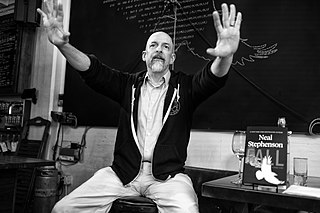

I try to find a style that matches the book. In the Baroque Cycle, I got infected with the prose style of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, which is my favorite era. It's recent enough that it is easy to read - easier than Elizabethan English - but it's pre-Victorian and so doesn't have the pomposity that is often a problem with 19th-century English prose. It is earthy and direct and frequently hilarious.

I really love James Joyce, Dubliners and other work. And I was interested in the way the dash was used in English topography - in his work particularly - and I realized there was no compulsion to use those ugly dot-dot curlicues all over the place to designate dialogue. I began to look around, and found writers who could make transitions quite clear by the language itself. I'm a bit of a maverick now. I'm always trying to push the medium.

The censors have always had a field day with James Joyce, specifically with 'Ulysses,' but also with his other writings. The conventional wisdom is that this is because of sexually explicit passages (and there certainly are those). I have always thought that what the critics hated and feared about Joyce is his cry for human freedom.

I've been working hard on [Ulysses] all day," said Joyce. Does that mean that you have written a great deal?" I said. Two sentences," said Joyce. I looked sideways but Joyce was not smiling. I thought of [French novelist Gustave] Flaubert. "You've been seeking the mot juste?" I said. No," said Joyce. "I have the words already. What I am seeking is the perfect order of words in the sentence.

You've probably heard about the theory of steam-engine time - that even after the steam engine had been invented, it had to wait until people were ready to make use of it. The same thing happens in literary circles. The truth is, I'm not terribly interested in Victorian times; I'm interested in Victorian writers. I'm interested in most eras of history, but not the Victorian Era especially. I was interested in the John Franklin Expedition. I was interested in these last five weird years of Dickens' life. And I just have to take the age that comes with all that when I write about it.

It's a historical thing, up to the 19th century the English hated the French. Then in the 20th century the English started to hate the Germans - as we began to move alphabetically through the map of the world. Now, the year 2000, we are fine with the Germans... but the Hungarians are pissing us off.