A Quote by Garry Winogrand

I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

In a world where the 2 billionth photograph has been uploaded to Flickr, which looks like an Eggleston picture! How do you deal with making photographs with the tens of thousands of photographs being uploaded to Facebook every second, how do you manage that? How do you contribute to that? What's the point?

Any photograph has multiple meanings: indeed, to see something in the form of a photograph is to encounter a potential object of fascination. The ultimate wisdom of the photographic image is to say: “There is the surface. Now think – or rather feel, intuit – what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.’ Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy

I think I’ve said this before many times—that photography allows you to learn to look and see. You begin to see things you had never paid any attention to. And as you photograph, one of the benefits is that the world becomes a much richer, juicier, visual place. Sometimes it is almost unbearable — it is too interesting. And it isn’t always just the photos you take that matters. It is looking at the world and seeing things that you never photograph that could be photographs if you had the energy to keep taking pictures every second of your life.

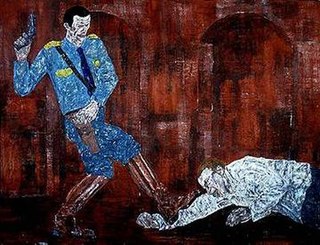

If you could see a photograph of what it took to make an advertising photograph - things you don't think about, like the photo assistant carefully arranging the meatballs - the degree of unnaturalness would be astonishing. Yet it produces an image that looks natural, and is orchestrated to provoke basic emotional responses.

But there is more to a fine photograph than information. We are also seeking to present an image that arouses the curiosity of the viewer or that, best of all, provokes the viewer to think-to ask a question or simply to gaze in thoughtful wonder. We know that photographs inform people. We also know that photographs move people. The photograph that does both is the one we want to see and make. It is the kind of picture that makes you want to pick up your own camera again and go to work.

The reason I do photographs is to help people understand my music, so it's very important that I am the same, emotionally, in the photographs as in the music. Most people's eyes are much better developed than their ears. If they see a certain emotion in the photograph, then they'll understand the music.

Because each photograph is only a fragment, its moral and emotional weight depends on where it is inserted. A photograph changes according to the context in which it is seen: thus Smith's Minamata photographs will seem different on a contact sheet, in a gallery, in a political demonstration, in a police file, in a photographic magazine, in a book, on a living-room wall. Each o these situations suggest a different use for the photographs but none can secure their meaning.