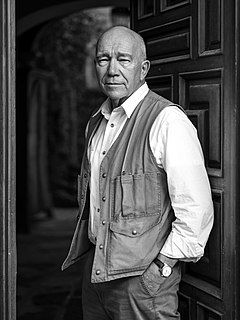

A Quote by Geoffrey Batchen

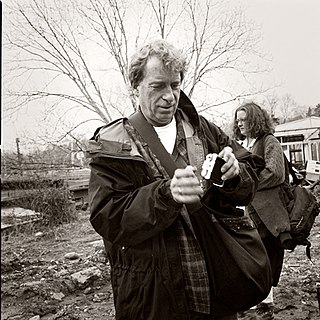

Human experience comes suspended in the sickly-sweet amniotic fluid of commercial photography. And a world normally animated by abrasive differences is blithely reduced to a single, homogeneous National Geographic way of seeing.

Related Quotes

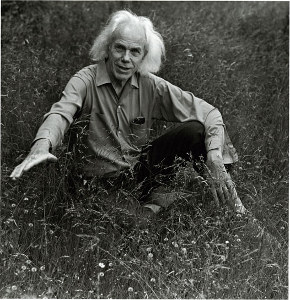

"You know you are seeing such a photograph if you say to yourself, "I could have taken that picture. I've seen such a scene before, but never like that." It is the kind of photography that relies for its strengths not on special equipment or effects but on the intensity of the photographer's seeing. It is the kind of photography in which the raw materials-light, space, and shape-are arranged in a meaningful and even universal way that gives grace to ordinary objects."