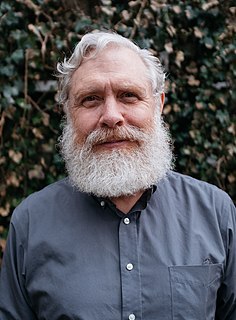

A Quote by George M. Church

The first thing you have to do is to sequence the Neanderthal genome, and that has actually been done. The next step would be to chop this genome up into, say, 10,000 chunks and then... assemble all the chunks in a human stem cell, which would enable you to finally create a Neanderthal clone.

Related Quotes

The question is, are there useful things that we can do with the results of a genome sequence that would bring benefit? And the answer is, today, should the majority of people go and have their genome sequenced? Probably not. But are there particular circumstances in which genome sequencing is really helpful? Yes, there are.

Every cell in our body, whether it's a bacterial cell or a human cell, has a genome. You can extract that genome - it's kind of like a linear tape - and you can read it by a variety of methods. Similarly, like a string of letters that you can read, you can also change it. You can write, you can edit it, and then you can put it back in the cell.

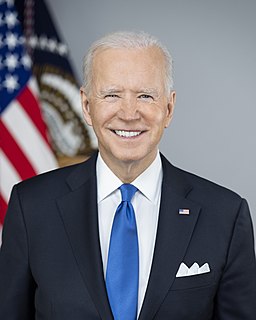

If I could get every single cancer genome sequence that has been sequenced; if I could ever put it in one repository, we have the capacity to do a million billion calculations per second. We'll be able to find out more in 10 minutes more than it would take 10 Nobel laureates 10 years to find out about the patterns of cancer and the cures for cancer.

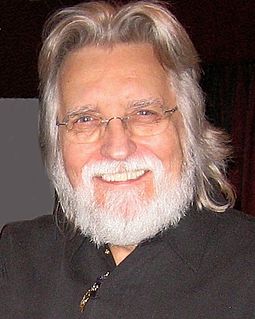

In science there is something known as a stem cell. A stem cell is an undifferentiated cell which has not yet decided whether it's gonna be a cell of your brain or a cell of your heart or of your finger nail. But science is learning how to coax, how to manipulate, the raw material of life that we call stem cell to become any cell of the body. I think that God is the stem cell of the universe.

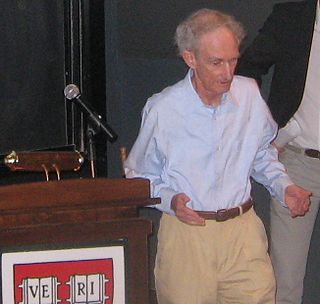

On one planet [earth], and possibly only one planet in the entire universe, molecules that would normally make nothing more complicated than a chunk of rock, gather themselves together into chunks of rock-sized matter of such staggering complexity that they are capable of running, jumping, swimming, flying, seeing, hearing, capturing and eating other such animated chunks of complexity; capable in some cases of thinking and feeling, and falling in love with yet other chunks of complex matter.

Recently, results of the Human Genome Project have shattered one of Science's fundamental core beliefs, the concept of genetic determinism. We have been led to believe that our genes determine the character of our lives, yet new research surprisingly reveals that it is the character of our lives that controls our genes. Rather than being victims of our heredity, we are actually masters of our genome.