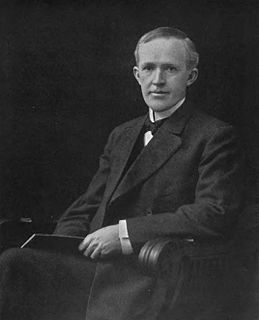

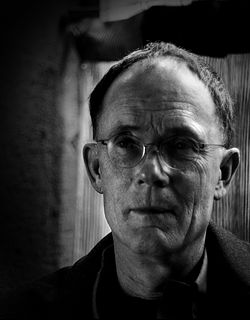

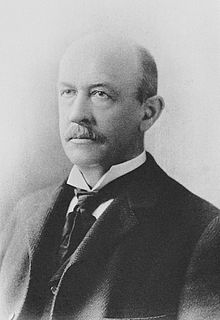

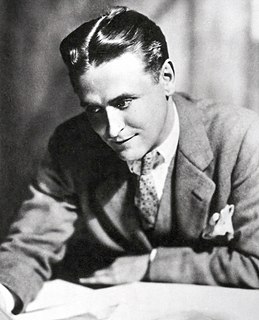

A Quote by George Orwell

The four great motives for writing prose are sheer egoism, esthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse, and political purpose.

Related Quotes

Enthusiasm needs to be effective enthusiasm. We must distinguish between the contribution and enthusiasm of the cheerleader and the enthusiasm of the player. While cheerleaders serve an important purpose, the real contest involves players on the field or on the court of life. We must not go through life acting only as enthusiastic cheerleaders available for hire; we must be anxiously and personally engaged.

In high school, in 1956, at the age of sixteen, we were not taught "creative writing." We were taught literature and grammar. So no one ever told me I couldn't write both prose and poetry, and I started out writing all the things I still write: poetry, prose fiction - which took me longer to get published - and non-fiction prose.