A Quote by George Polya

The principle is so perfectly general that no particular application of it is possible.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

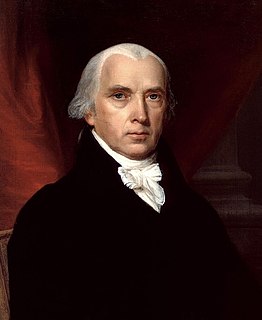

Money cannot be applied to the *general welfare*, otherwise than by an application of it to some *particular* measure conducive to the general welfare. Whenever, therefore, money has been raised by the general authority, and is to be applied to a particular measure, a question arises whether the particular measure be within the enumerated authorities vested in Congress. If it be, the money requisite for it may be applied to it; if it be not, no such application can be made.

There is a great difference, whether the poet seeks the particular for the sake of the general or sees the general in the particular. From the former procedure there ensues allegory, in which the particular serves only as illustration, as example of the general. The latter procedure, however, is genuinely the nature of poetry; it expresses something particular, without thinking of the general or pointing to it.

Kantian ethical theory distinguishes three levels: First, that of a fundamental principle (the categorical imperative, formulated in three main ways in Kant's Groundwork); second, a set of duties, not deduced from but derived from this principle, by way of its interpretation or specification, its application to the general conditions of human life - which Kant does in the Doctrine of virtue, the second main part of the Metaphysics of Morals; and then finally an act of judgment, through which these duties are applied to particular cases.

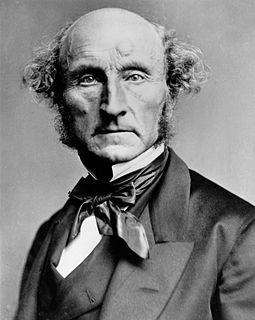

The principle itself of dogmatic religion, dogmatic morality, dogmatic philosophy, is what requires to be rooted out; not any particular manifestation of that principle. The very corner-stone of an education intended to form great minds, must be the recognition of the principle, that the object is to call forth the greatest possible quantity of intellectual power, and to inspire the intensest love of truth.

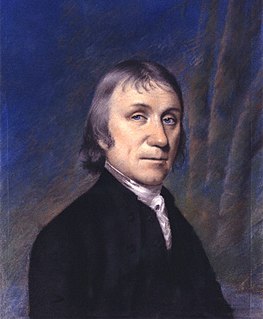

First, it is necessary to study the facts, to multiply the number of observations, and then later to search for formulas that connect them so as thus to discern the particular laws governing a certain class of phenomena. In general, it is not until after these particular laws have been established that one can expect to discover and articulate the more general laws that complete theories by bringing a multitude of apparently very diverse phenomena together under a single governing principle.

In the loss of skill, we lose stewardship; in losing stewardship we lose fellowship; we become outcasts from the great neighborhood of Creation. It is possible - as our experience in this good land shows - to exile ourselves from Creation, and to ally ourselves with the principle of destruction - which is, ultimately, the principle of nonentity. It is to be willing in general for being to not-be. And once we have allied ourselves with that principle, we are foolish to think that we can control the results. (pg. 303, The Gift of Good Land)

Tis not the wholesome sharp mortality,

Or modest anger of a satiric spirit,

That hurts or wounds the body of a state,

But the sinister application

Of the malicious, ignorant, and base

Interpreter; who will distort and strain

The general scope and purpose of an author

To his particular and private spleen.