A Quote by George R. R. Martin

She might have wept then, had not the sky begun to do it for her.

Related Quotes

The pain was as unexpected as a thunderclap in a clear sky. Eddis's chest tightened, as something closed around her heart. A deep breath might have calmed her, but she couldn't draw one. She wondered if she was ill, and she even thought briefly that she might have been poisoned. She felt Attolia reach out and take her hand. To the court it was unexceptional, hardly noticed, but to Eddis it was an anchor, and she held on to it as if to a lifeline. Sounis was looking at her with concern. Her responding smile was artificial.

Staring at her face, she began to fancy her outer layer had begun to melt away while she wasn't paying attention, and something -- some new skeleton -- was emerging from beneath the softness of her accustomed self. With a deep, visceral ache, she wished her true form might prove to be a sleek and shining one, like a stiletto blade slicing free of an ungainly sheath. Like a bird of prey losing its hatchling fluff to hunt in cold, magnificent skies. That she might become something glittering, something startling, something dangerous.

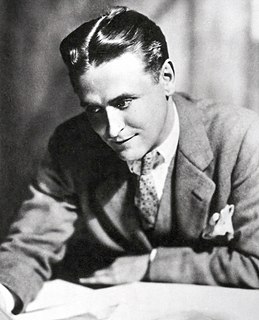

She felt a stealing sense of fatigue as she walked; the sparkle had died out of her, and the taste of life was stale on her lips. She hardly knew what she had been seeking, or why the failure to find it had so blotted the light from her sky: she was only aware of a vague sense of failure, of an inner isolation deeper than the loneliness about her.

In a way, her strangeness, her naiveté, her craving for the other half of her equation was the consequence of an idle imagination. Had she paints, or clay, or knew the discipline of the dance, or strings, had she anything to engage her tremendous curiosity and her gift for metaphor, she might have exchanged the restlessness and preoccupation with whim for an activity that provided her with all she yearned for. And like an artist with no art form, she became dangerous.

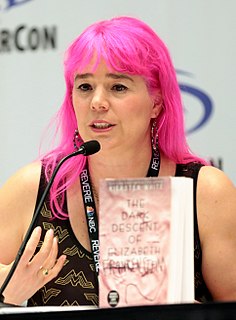

Tessa had begun to tremble. This is what she had always wanted someone to say. What she had always, in the darkest corner of her heart, wanted Will to say. Will, the boy who loved the same books she did, the same poetry she did, who made her laugh even when she was furious. And here he was standing in front of her, telling her he loved the words of her heart, the shape of her soul. Telling her something she had never imagined anyone would ever tell her. Telling her something she would never be told again, not in this way. And not by him. And it did not matter. "It's too late", she said.

She is nine, beloved, as open-faced as the sky and as self-contained. I have watched her grow. As recently as three or four years ago, she had a young child's perfectly shallow receptiveness; she fitted into the world of time, it fitted into her, as thoughtlessly as sky fits its edges, or a river its banks. But as she has grown, her smile has widened with a touch of fear and her glance has taken on depth. Now she is aware of some of the losses you incur by being here--the extortionary rent you have to pay as long as you stay.

...she wasn't reading Deathly Hallows at all. Her book wasn't orange but rose and water and sand, and featured a kid on a broomstick and white unicorn. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. She didn't notice me staring at her. 'Oh, I envy you,' I thought, but was smiling for her. She had just begun.

How sadly things had changed since she had sat there the night after coming home! Then she had been full of hope and joy and the future had looked rosy with promise. Anne felt as if she had lived years since then, but before she went to bed there was a smile on her lips and peace in her heart. She had looked her duty courageously in the face and found it a friend--as duty ever is when we meet it frankly.

Fine,' Aria conceded. 'But *I'll* carry her.' She grabbed the baby seeat from the back. A smell of baby powder wafted up to greet her, bringing a lump in her throat. Her father Byron, and his girlfriend, Meredith, had just had a baby, and she loved Lola with all her heart. If she looked too long at this baby, she might love her just as much.

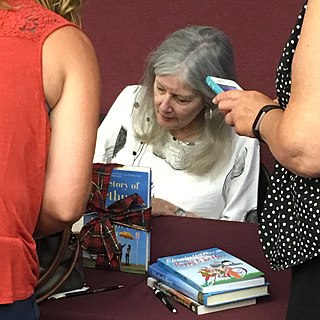

In the classics section, she had picked up a copy of The Magic Mountain and recalled the summer between her junior and senior years of high school, when she read it, how she lay in bed hours after she should have gotten up, the sheet growing warmer against her skin as the sun rose higher in the sky, her mother poking her head in now and then to see if she'd gotten up yet, but never suggesting that she should: Eleanor didn't have many rules about child rearing, but one of them was this: Never interrupt reading.

She didn't like to be talked about. Equally, she didn't like not to be talked about, when the high-minded chatter rushed on as though she was not there. There was no pleasing her, in fact. She had the grace, even at eleven, to know there was no pleasing her. She thought a lot, analytically, about other people's feelings, and had only just begun to realize that this was not usual, and not reciprocated.

At that moment a very good thing was happening to her. Four good things had happened to her, in fact, since she came to Misselthwaite Manor. She had felt as if she had understood a robin and that he had understood her; she had run in the wind until her blood had grown warm; she had been healthily hungry for the first time in her life; and she had found out what it was to be sorry for someone.

She had had her momentary flowering, a year, perhaps, of wildrose beauty, and then she had suddenly swollen like a fertilized fruit and grown hard and red and coarse, and then her life had been laundering, scrubbing, laundering, first for children, then for grandchildren, over thirty years. At the end of it she was still singing.

I get goose-bumps when you talk about Diane Wilson. Who knows where she found that courage? When she was a child, she would crawl under the bed when a stranger came to the house. But in 1989, she found out that her county in south Texas was ranked worst in the country for toxic waste. She wondered if the effluent, dumped into the waters where she and her family had shrimped for generations, might be responsible for the dwindling fish populations. And she suspected that her son's autism might be related to the pollution.