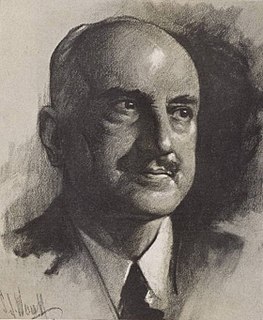

A Quote by George Santayana

Experience seems to most of us to lead to conclusions, but empiricism has sworn never to draw them.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

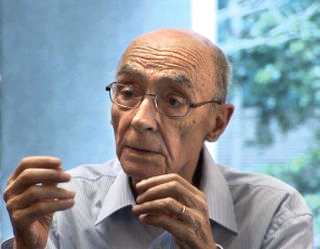

It is not often that nations learn from the past even rarer that they draw the correct conclusions from it. For the lessons of historical experience, as of personal experience, are contingent. They teach the consequences of certain actions, but they cannot force a recognition of comparable situations.

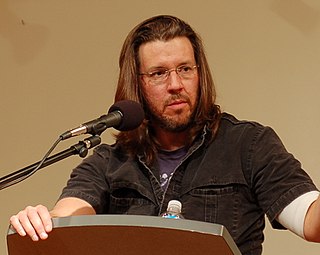

I'm a self trained, autodidactic artist, so all I was ever trying to do was to draw as realistically as possible - but that's what comes out, because I don't really know how to draw! I think when I draw characters, I'm able to reduce them down to little marks that capture the most distinct elements of them.

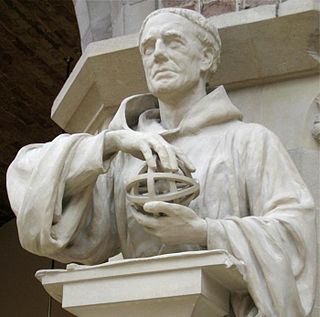

It is not enough to say that we cannot know or judge because all the information is not in. The process of gathering knowledge does not lead to knowing. A child's world spreads only a little beyond his understanding while that of a great scientist thrusts outward immeasurably. An answer is invariably the parent of a great family of new questions. So we draw worlds and fit them like tracings against the world about us, and crumple them when we find they do not fit and draw new ones.