A Quote by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

He [man] abuses equally other animals and his own species, the rest of whom live in famine, languish in misery, and work only to satisfy the immoderate appetite and the still more insatiable vanity of this human being who, destroying others by want, destroys himself by excess.

Related Quotes

The earth is not a mechanism but an organism, a being with its own life and its own reasons, where the support and sustenance of the human animal is incidental. If man in his newfound power and vanity persists in the attempt to remake the planet in his own image, he will succeed only in destroying himself - not the planet. The earth will survive our most ingenious folly.

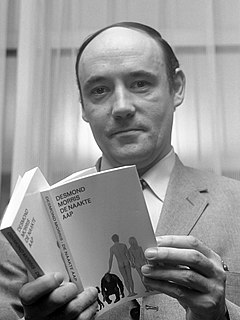

It must be stressed that there is nothing insulting about looking at people as animals. We are animals, after all. Homo sapiens is a species of primate, a biological phenomenon dominated by biological rules, like any other species. Human nature is no more than one particular kind of animal nature. Agreed, the human species is an extraordinary animal; but all other species are also extraordinary animals, each in their own way, and the scientific man-watcher can bring many fresh insights to the study of human affairs if he can retain this basic attitude of evolutionary humility.

Man—every man—is an end in himself, not a means to the ends of others; he must live for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself; he must work for his rational self-interest, with the achievement of his own happiness as the highest moral purpose of his life.

Theoretically, the actor ought to be more sound in mind and body than other people, since he learns to understand the psychological problems of human beings when putting his own passions, his loves, fears, and rages to work in the service of the characters he plays. He will learn to face himself, to hide nothing from himself- and to do so takes AN INSATIABLE CURIOSITY ABOUT THE HUMAN CONDITION

The ruling British elite are like animals--not only in their morality, but in their outlook on knowledge. They are clever animals, who are masters of the wicked nature of their own species, and recognize ferally the distinctions of the hated human species. Nonetheless, obsessively dedicated to being such animals, they can not [sic] assimilate those qualities unique to true human beings.

It is natural for every man uninstructed to murmur at his condition, because, in the general infelicity of life, he feels his own miseries without knowing that they are common to all the rest of the species; and, therefore, though he will not be less sensible of pain by being told that others are equally tormented, he will at least be freed from the temptation of seeking, by perpetual changes, that ease which is no where to be found, and though his diseases still continue, he escapes the hazard of exasperating it by remedies.

In a community of human beings working together, the well-being of the community will be the greater, the less the individual claims for himself the proceeds of the work he has himself done; i.e., the more of these proceeds he makes over to his fellow workers, and the more his own requirements are satisfied, not out of his own work done, but out of work done by the others.

Every man is of importance to himself, and, therefore, in his own opinion, to others; and, supposing the world already acquainted with his pleasures and his pains, is perhaps the first to publish injuries or misfortunes which had never been known unless related by himself, and at which those that hear them will only laugh, for no man sympathises with the sorrows of vanity.

If a young man gets married, and starts a family and spends the rest of his life working at a soul-destroying job, he is held up as an example of virtue and responsibility. The other type of man, living only for himself, working only for himself, doing first one thing and then another simply because he enjoys it and because he has to keep only himself, sleeping where and when he wants, and facing woman when he meets her on equal terms and not as one of a million slaves, is rejected by society. The free, unshackled man has no place in its midst.

He brings to naught, destroys and rejects all that is not His own work; how He draws everything to Himself and absorbs it, that at last He may live and work in us and through us and reign alone as king. Happy the soul who refuses nothing to love, but places everything at His disposal, for only thus may all our works be done more and more in God.

There are three kinds of nature in man, as Nicetas Stethatos further explains: the carnal man, who wants to live for his own pleasure, even if it harms others; the natural man, who wants to please both himself and others; and the spiritual man, who wants to please only God, even if it harms himself. The first is lower than human nature, the second is normal, the third is above nature; it is life in Christ.

The man who works recognizes his own product in the world that has actually been transformed by his work. He recognizes himself in it, he sees his own human reality in it he discovers and reveals to others the objective reality of his humanity of the originally abstract and purely subjective idea he has of himself

Only when there is a wilderness can man harmonize his inner being with the wavelengths of the earth. When the earth, its products, its creatures, become his concern, man is caught up in a cause greater than his own life and more meaningful. Only when man loses himself in an endeavor of that magnitude does he walk and live with humanity and reverence.

Man is merely a frequent effect, a monstrosity is a rare one, but both are equally natural, equally inevitable, equally part of the universal and general order. And what is strange about that? All creatures are involved in the life of all others, consequently every species... all nature is in a perpetual state of flux. Every animal is more or less a human being, every mineral more or less a plant, every plant more or less an animal... There is nothing clearly defined in nature.