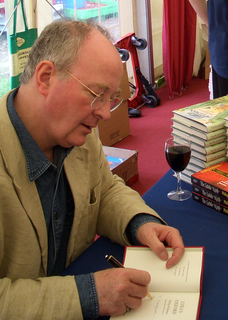

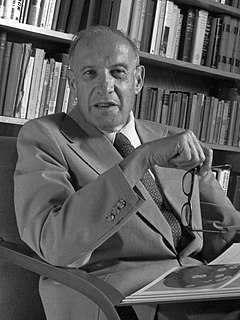

A Quote by Gordon Getty

My music is all about an idealistic human personality. I have 19th-century ideals.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

There is not one particular moment that can account for the shift from the social issue concerns of 19th-century evangelicals into the state of American evangelicalism today. Some historical moments are telling. The rise of biblical criticism in the 19th century forced evangelicals to make choices about what they believed about the gospel.

People have asked me about the 19th century and how I knew so much about it. And the fact is I really grew up in the 19th century, because North Carolina in the 1950s, the early years of my childhood, was exactly synchronous with North Carolina in the 1850s. And I used every scrap of knowledge that I had.

I was really interested in 20th century communalism and alternative communities, the boom of communes in the 60s and 70s. That led me back to the 19th century. I was shocked to find what I would describe as far more utopian ideas in the 19th century than in the 20th century. Not only were the ideas so extreme, but surprising people were adopting them.

The different American experience of the 20th Century is crucial because the lesson of the century for Europe, which essentially is that the human condition is tragic, led it to have a build a welfare system and a set of laws and social arrangements that are more prophylactic than idealistic. It's not about building perfect futures; it's about preventing terrible pasts. I think that is something that Europeans in the second half of the 20th century knew in their bones and Americans never did, and it's one of the big differences between the two Western cultures.

The Anglo-American tradition is much more linear than the European tradition. If you think about writers like Borges, Calvino, Perec or Marquez, they're not bound in the same sort of way. They don't come out of the classic 19th-century novel, which is where all the problems start. 19th-century novels are fabulous and we should all read them, but we shouldn't write them.