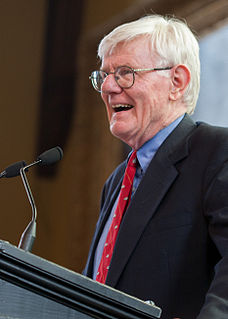

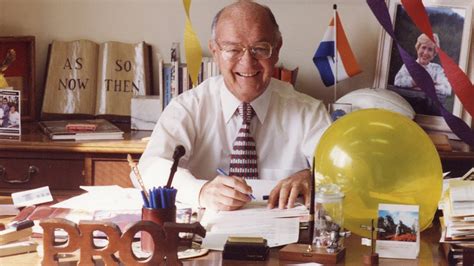

A Quote by Gordon S. Wood

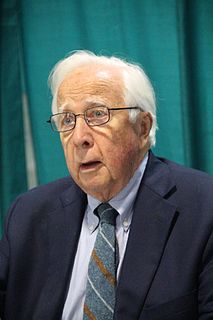

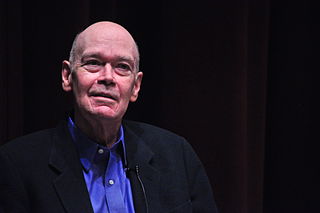

The relationship between [John] Adams and [Tomas] Jefferson was extraordinary. They differed on every conceivable issue, except on the Revolution and the love of their country.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

[John Adams and Tomas Jefferson] shared experience in 1775 - 1776 in bringing about the separation from Britain and their service in Europe cemented a friendship that in the end withstood the most serious political and religious differences that one could imagine, especially their differences over the French Revolution. It was probably Jefferson's obsession with politeness and civility that kept the relationship from becoming irreparably broken.

[John] Adams's perception of Europe, and especially France, was clearly different than [Tomas] Jefferson's. For Jefferson, the luxury and sophistication of Europe only made American simplicity and virtue appear dearer. For Adams, by contrast, Europe represented what America was fast becoming - a society consumed by luxury and vice and fundamentally riven by a struggle between rich and poor, gentlemen and commoners.

According to Adams, Jefferson proposed that he, Adams, do the writing [pf the Declaration of Independence], but that he declined, telling Jefferson he must do it. Why?" Jefferson asked, as Adams would recount. Reasons enough," Adams said. What can be your reasons?" Reason first: you are a Virginian and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second: I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third: You can write ten times better than I can.

The presidency made John Adams an old man long before there was television. As early as the nation's first contested presidential election, with Adams and Jefferson running to succeed Washington, you had a brutal, ugly, vicious campaign that was divisive and as partisan as anything we're experiencing today.