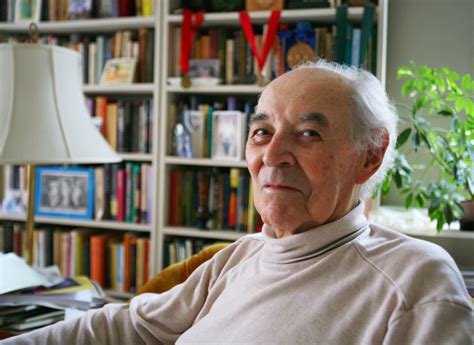

A Quote by Gregory Rabassa

I have always maintained that translation is essentially the closest reading one can possibly give a text. The translator cannot ignore "lesser" words, but must consider every jot and tittle.

Related Quotes

I think that if you are sticking to the text, essentially, you're not trying to write your own version of it. I mean, of course, it is your own version of it. And every translator would probably have a different version. But I think that that's what keeps the writers from being individual in English. They may be my English, but I don't think that Ferrante sounds like Levi.

The reader must come armed , in a serious state of intellectual readiness. This is not easy because he comes to the text alone. In reading, one's responses are isolated, one'sintellect thrown back on its own resourses. To be confronted by the cold abstractions of printed sentences is to look upon language bare, without the assistance of either beauty or community. Thus, reading is by its nature a serious business. It is also, of course, an essentially rational activity.

You must remember always to give, of everything you have. You must give foolishly even. You must be extravagant. You must give to all who come into your life. Then nothing and no one shall have power to cheat you of anything, for if you give to a thief, he cannot steal from you, and he himself is then no longer a thief. And the more you give, the more you will have to give.

In translation studies we talk about domestication - translation styles that make something familiar - or estrangement - translation styles that make something radically different. I use a lot of both in my translation, and modernism does both. For instance, if you look at the way James Joyce presents Ulysses, is that domesticating a classic? Think of it as an experiment in relation to a well-known text in another language.