A Quote by Gretel Ehrlich

History is not truth versus falsehoods, but a mixture of both, a mélange of tendencies, reactions, dreams, errors, and power plays. What's important is what we make of it; its moral use. By writing history, we can widen readers' thinking and deepen their sympathies in every direction. Perhaps history should show us not how to control the world, but how to enlarge, deepen, and discipline ourselves.

Related Quotes

The value of history is, indeed, not scientific but moral: by liberalizing the mind, by deepening the sympathies, by fortifying the will, it enables us to control, not society, but ourselves - a much more important thing; it prepares us to live more humanely in the present and to meet rather than to foretell the future.

I get letters from two kinds of readers. History buffs, who love to read history and biography for fun, and then kids who want to be writers but who rarely come out and say so in their letters. You can tell by the questions they ask - How did you get your ?rst book published? How long do you spend on a book? So I guess those are the readers that I'm writing for - kids who enjoy that kind of book, because they're interested in history, in other people's lives, in what has happened in the world. I believe that they're the ones who are going to be the movers and shakers.

I don't even know in American educational history classes how much of D-Day, World War II, all of that is taught versus how much of it is just ignored or looked back on with mockery or insincerity or what have you. But it was one of the most crucially important events in all of human history in terms of the preservation of freedom and liberty and the notion of democracy and things associated with it.

I consider myself a progressive, so my answer would be that we need to be progressive. For some reason the people in power in Mississippi still seem to be invested in these very American myths."The individual is alone." "We pull ourselves up by our bootstraps." "We create success for ourselves, and if we work hard enough then we will succeed and have success beyond our wildest dreams." I think that we need to do away with that kind of thinking and be more aware of history and how the history of this place bears in the present and how it affects people.

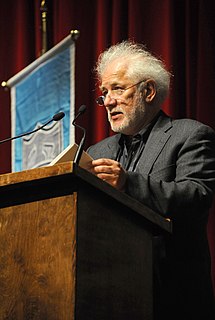

My book, Oral History: Understanding Qualitative Research is about how researchers use this method and how to write up their oral history projects so that audiences can read them. It's important that researchers have many different tools available to study people's lives and the cultures we live in. I think oral history is a most needed and uniquely important strategy.

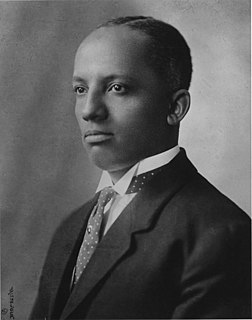

We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world, void of national bias, race, hate, and religious prejudice. There should be no indulgence in undue eulogy of the Negro. The case of the Negro is well taken care of when it is shown how he has far influenced the development of civilization.

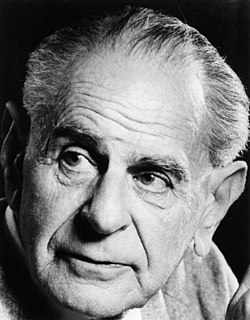

The history of science, like the history of all human ideas, is a history of irresponsible dreams, of obstinacy, and of error. But science is one of the very few human activities-perhaps the only one-in which errors are systematically criticized and fairly often, in time, corrected. This is why we can say that, in science, we often learn from our mistakes, and why we can speak clearly and sensibly about making progress there. In most other fields of human endeavour there is change, but rarely progress ... And in most fields we do not even know how to evaluate change.

You are doing something over here and over there someone is telling you a joke, or giving you an important piece of information about sanitation, and no matter how weird the other subject is, there is a connection, or you can make a connection. I’ve always loved history and history is collage, it is a juxtaposition of the good and the bad and the strange, and how you place those sentences together changes the whole mood of a history.

Even those who specialize in the history of philosophy often ignore the political and cultural context, and the natural world in which their philosophers were philosophizing. This has consequences both trivial and important. If you systematically read the last fifty years of the major journals in our discipline you would be amazed at the amount of redundancy. Most of this is unacknowledged because most of us know so little about the history of our discipline and even the subfields in which we work.

You could make a good case that the history of social life is about the history of the technology of memory. That social order and control, structure of governance, social cohesion in states or organizations larger than face-to-face society depends on the nature of the technology of memory - both how it works and what it remembers. In short, what societies value is what they memorize, and how they memorize it, and who has access to its memorized form determines the structure of power that the society represents and acts from.