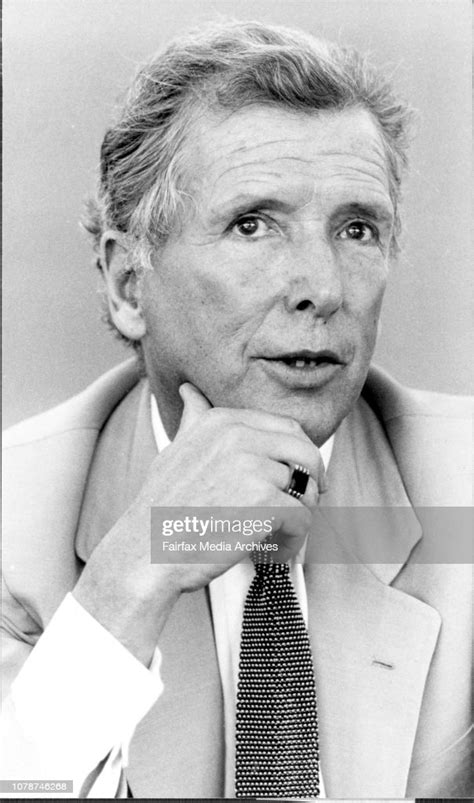

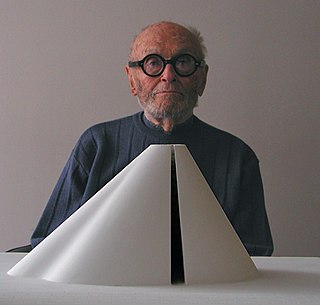

A Quote by Harry Seidler

The form language used by the ancient Egyptians in their structures is minimal.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Do the structures of language and the structures of reality (by which I mean what actually happens) move along parallel lines? Does reality essentially remain outside language, separate, obdurate, alien, not susceptible to description? Is an accurate and vital correspondence between what is and our perception of it impossible? Or is it that we are obliged to use language only in order to obscure and distort reality -- to distort what happens -- because we fear it?

I think that metaphor really is a key to explaining thought and language. The human mind comes equipped with an ability to penetrate the cladding of sensory appearance and discern the abstract construction underneath - not always on demand, and not infallibly, but often enough and insightfully enough to shape the human condition. Our powers of analogy allow us to apply ancient neural structures to newfound subject matter, to discover hidden laws and systems in nature, and not least, to amplify the expressive power of language itself.

Lying is the misuse of language. We know that. We need to remember that it works the other way round too. Even with the best intentions, language misused, language used stupidly, carelessly, brutally, language used wrongly, breeds lies, half-truths, confusion. In that sense you can say that grammar is morality. And it is in that sense that I say a writer's first duty is to use language well.