A Quote by Henry David Thoreau

Homeliness is almost as great a merit in a book as in a house, if the reader would abide there. It is next to beauty, and a very high art.

Related Quotes

There is a sort of homely truth and naturalness in some books which is very rare to find, and yet looks cheap enough. There may benothing lofty in the sentiment, or fine in the expression, but it is careless country talk. Homeliness is almost as great a merit in a book as in a house, if the reader would abide there. It is next to beauty, and a very high art. Some have this merit only.

Every reader, as he reads, is actually the reader of himself. The writer's work is only a kind of optical instrument he provides the reader so he can discern what he might never have seen in himself without this book. The reader's recognition in himself of what the book says is the proof of the book's truth.

The refining influence is the study of art, which is the science of beauty; and I find that every man values every scrap of knowledge in art, every observation of his own in it, every hint he has caught from another. For the laws of beauty are the beauty of beauty, and give the mind the same or a higher joy than the sight of it gives the senses. The study of art is of high value to the growth of the intellect.

I would suppose I learned how to write when I was very young indeed. When I read a child's book about the Trojan War and decided that the Greeks were really a bunch of frauds with their tricky horses and the terrible things they did, stealing one another's wives, and so on, so at that very early age, I re-wrote the ending of the Iliad so that the Trojans won. And boy, Achilles and Ajax got what they wanted, believe me. And thereafter, at frequent intervals, I would write something. It was really quite extraordinary. Never of very high merit, but the daringness of it was.

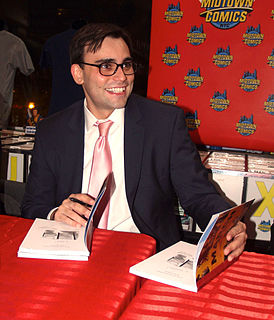

In my couple of books, including Going Clear, the book about Scientology, I thought it seemed appropriate at the end of the book to help the reader frame things. Because we've gone through the history, and there's likely conflictual feelings in the reader's mind. The reader may not agree with me, but I don't try to influence the reader's judgment. I know everybody who picks this book up already has a decided opinion. But my goal is to open the reader's mind a little bit to alternative narratives.

But I am not sure it would contain any short stories. For the short story is a minor art, and it must content itself with moving, exciting and amusing the reader. ...I do not think that there is any (short story) that will give the reader that thrill, that rapture, that fruitful energy which great art can produce.

Intellectual culture seems to separate high art from low art. Low art is horror or pornography or anything that has a physical component to it and engages the reader on a visceral level and evokes a strong sympathetic reaction. High art is people driving in Volvos and talking a lot. I just don't want to keep those things separate. I think you can use visceral physical experiences to illustrate larger ideas, whether they're emotional or spiritual. I'm trying to not exclude high and low art or separate them.

I can tell that I shaped the book very deliberately, after a great deal of thought, and that I insisted this piece function as a prologue, but I find the word "intention," confusing ("trust the art," as D.H. Lawrence said, "not the artist"). These speculations are perhaps better responded to by text and reader, rather than author.

A book is one of the most patient of all man's inventions. Centuries mean nothing to a well-made book. It awaits its destined reader, come when he may, with eager hand and seeing eye. Then occurs one of the great examples of union, that of a man with a book, pleasurable, sometimes fruitful, potentially world-changing, simple; and in a library...witho ut cost to the reader.