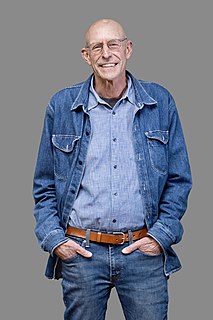

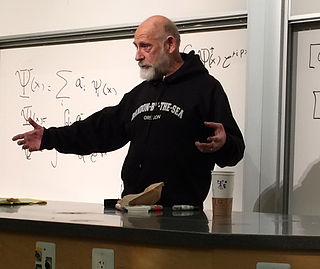

A Quote by Henry Stapp

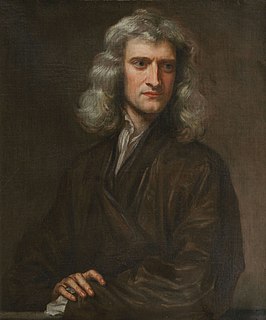

An elementary particle is not an independently existing, unanalyzable entity. It is, in essence, a set of relationships that reaches outward to other things.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Value investors will not invest in businesses that they cannot readily understand or ones they find excessively risky. Hence few value investors will own the shares of technology companies. Many also shun commercial banks, which they consider to have unanalyzable assets, as well as property and casualty insurance companies, which have both unanalyzable assets and liabilities.

It is true (independently of our conceptualisation) that it is wrong to inflict pain on a sentient creature for no reason (she doesn't deserve it, I haven't promised to do it, it is not helpful to this creature or to anyone else if I do it, and so forth). But if this is a truth, existing independently of our conceptualisation, then at least one moral fact (this one) exists and moral realism is true. We have to accept this, I submit, unless we can find strong reasons to think otherwise.

We affect one another quite enough merely by existing. Whenever the stars cross, or is it comets? fragments pass briefly from one orbit to another. On rare occasions there is total collision, but most often the two simply continue without incident, neither losing more than a particle to the other, in passing.