A Quote by Hillary Clinton

The public trust is at the core of both a free market economy and a democracy.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

It is eminently possible to have a market-based economy that requires no such brutality and demands no such ideological purity. A free market in consumer products can coexist with free public health care, with public schools, with a large segment of the economy -- like a national oil company -- held in state hands. It's equally possible to require corporations to pay decent wages, to respect the right of workers to form unions, and for governments to tax and redistribute wealth so that the sharp inequalities that mark the corporatist state are reduced. Markets need not be fundamentalist.

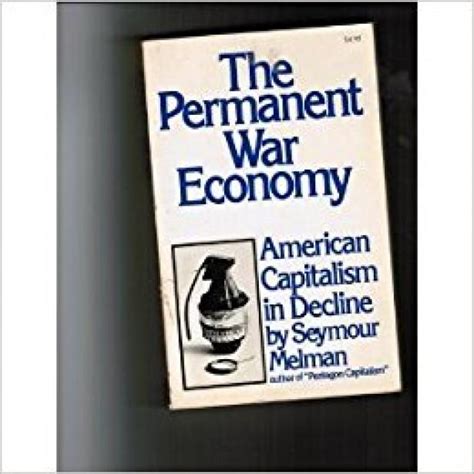

There is no use in deceiving ourselves. American public opinion rejects the market economy, the capitalistic free enterprise system that provided the nation with the highest standard of living ever attained. Full government control of all activities of the individual is virtually the goal of both national parties.

Today it's fashionable to talk about the New Economy, or the Information Economy, or the Knowledge Economy. But when I think about the imperatives of this market, I view today's economy as the Value Economy. Adding value has become more than just a sound business principle; it is both the common denominator and the competitive edge.