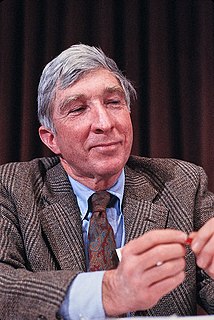

A Quote by Ian Hacking

Until the seventeenth century there was no concept of evidence with which to pose the problem of induction!

Related Quotes

It is time, therefore, to abandon the superstition that natural science cannot be regarded as logically respectable until philosophers have solved the problem of induction. The problem of induction is, roughly speaking, the problem of finding a way to prove that certain empirical generalizations which are derived from past experience will hold good also in the future.

The kind of knowledge which is supported only by observations and is not yet proved must be carefully distinguished from the truth; it is gained by induction, as we usually say. Yet we have seen cases in which mere induction led to error. Therefore, we should take great care not to accept as true such properties of the numbers which we have discovered by observation and which are supported by induction alone. Indeed, we should use such a discovery as an opportunity to investigate more exactly the properties discovered and to prove or disprove them; in both cases we may learn something useful.