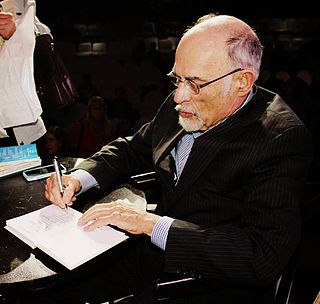

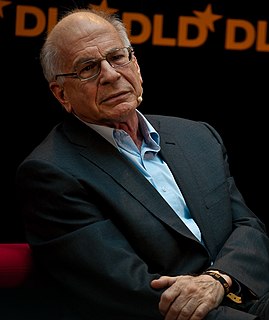

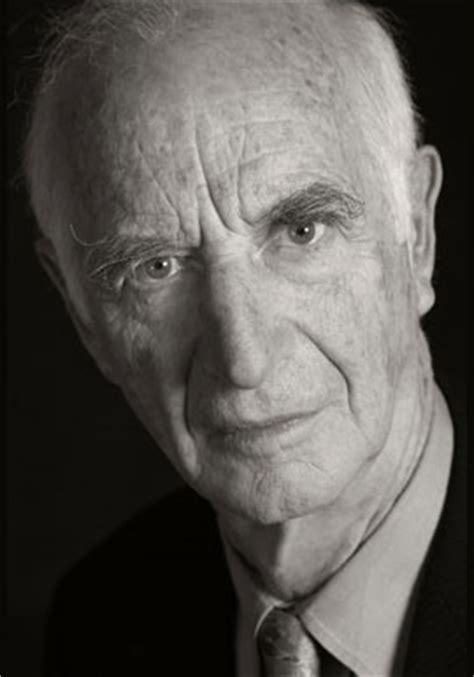

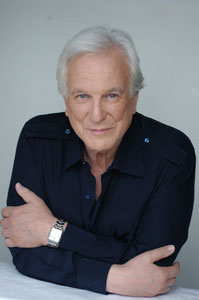

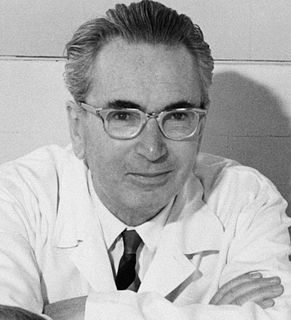

A Quote by Irvin D. Yalom

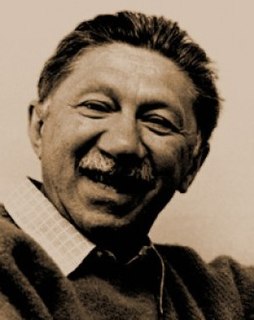

One doesn't do existential therapy as a freestanding separate theory; rather it informs your approach to such issues as death, which many therapists tend to shy away from.

Related Quotes

I studied Sanskrit for many years, and I've got all the coursework for my Ph.D. And a lot of what's going on in American Yoga is just made-up stuff. Smart people, even good people, Western therapists, Yoga therapists and other things, Western healthcare practitioners who love Asana and say, "Let's make up yoga therapy."

Our approach to existential risks cannot be one of trial-and-error. There is no opportunity to learn from errors. The reactive approach - see what happens, limit damages, and learn from experience - is unworkable. Rather, we must take a proactive approach. This requires foresight to anticipate new types of threats and a willingness to take decisive preventive action and to bear the costs (moral and economic) of such actions.

Gangsters live for the action. The closer to death, the nearer to the heated coil of the moment, the more alive they feel. Most would rather succumb to a barrage of bullets from a roomful of sworn enemies than to the debilitation of old age, dying the death of the feeble. A gangster becomes as addicted to the thrill of the battle and the potential to die in the midst of it as he does to he more attractive lures in his path. In his world, the potential for death exists every day. The better gangsters don't shy away from such a dreaded possibility but rather find comfort in its proximity.

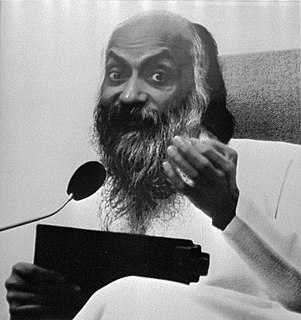

People are not afraid of death, they are afraid of losing their separation, they are afraid of losing their ego. Once you start feeling separate from existence the fear of death arises because then death seems to be dangerous. You will no longer be separate; what will happen to your ego, your personality? And you have cultivated the personality with such care, with such great effort; you have polished it your whole life, and death will come and destroy it

Nobody will protect you from your suffering. You can't cry it away or eat it away or starve it away or walk it away or punch it away or even therapy it away. It's just there, and you have to survive it. You have to endure it. You have to live through it and love it and move on and be better for it and run as far as you can in the direction of your best and happiest dreams across the bridge that was built by your own desire to heal.

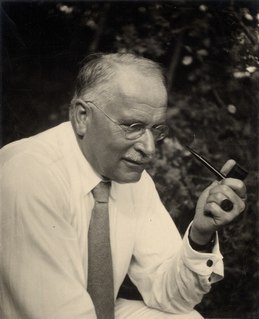

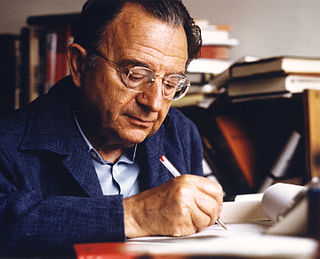

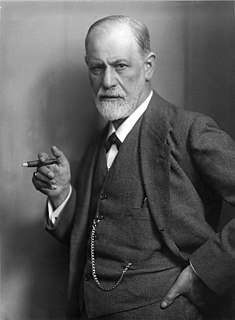

The main interest of my work is not concerned with the treatment of neuroses but rather with the approach to the numinous. But the fact that the approach to the numinous is the real therapy, and inasmuch as you attain to the numinous experience you are released from the curse of pathology. Even the very disease takes on a numinous character.

Now on to reparative therapy, I think counseling is a wonderful tool for anybody regardless of what struggle they bring to the table. I think we can all use a little bit of counseling on planet earth today. But when it comes to reparative therapy, the reason we have distanced ourselves from it is because some of the things that they employ and some of the messages that I've heard from reparative therapists with regards to what someone can expect once they get through that type of therapy.

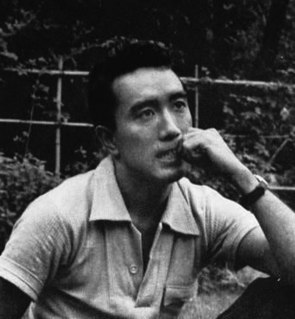

We tend to suffer from the illusion that we are capable of dying for a belief or theory. What Hagakure is insisting is that even in merciless death, a futile death that knows neither flower nor fruit has dignity as the death of a human being. If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.

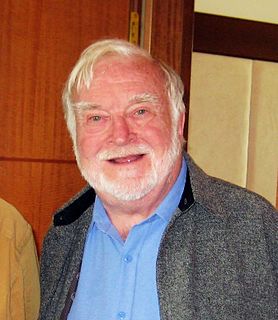

I have known know many therapists who come out of Pacifica Graduate Institute and love being both artists and therapists at the same time, like Maureen Murdock. They are photographers and dancers and other kinds of things and therapists at the same time. I think it really makes them a much more interesting therapist because they're so engaged with the imagination and the creativity and the depths of who they are.