A Quote by Isaac Asimov

Jokes of the proper kind, properly told, can do more to enlighten questions of politics, philosophy, and literature than any number of dull arguments.

Related Quotes

Quite early on, and certainly since I started writing, I found that philosophical questions occupied me more than any other kind. I hadn't really thought of them as being philosophical questions, but one rapidly comes to an understanding that philosophy's only really about two questions: 'What is true?' and 'What is good?'

In the history and literature courses I took, epistemological questions came to interest me most. What makes one explanation of the French Revolution better than another? What makes one interpretation of "Waiting for Godot" better than another? These questions led me to philosophy and then to philosophy of science.

Some of my understanding of what philosophy and ethics is has changed very slowly. One thing that has changed is this for quite a long time I bought-into the idea that philosophy is basically about arguments. I'm increasingly of the view that it isn't. The most interesting things in philosophy aren't arguments. The thing that I think is underestimated is what I call a form of attending. I think that philosophy is at least as much about carefully attending to things as it is about the structure of arguments.

Long ago, during my apprenticeship in the wine trade, I learned that wine is more than the sum of its parts, and more than an expression of its physical origin. The real significance of wine as the nexus of just about everything became clearer to me when I started writing about it. The more I read, the more I traveled, and the more questions I asked, the further I was pulled into the realms of history and economics, politics, literature, food, community, and all else that affects the way we live. Wine, I found, draws on everything and leads everywhere.

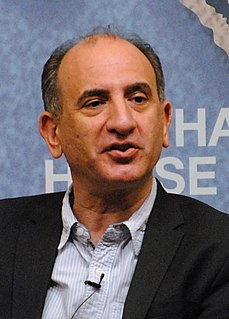

I think it's a slightly crazy time actually, it's very difficult to satirise because each of politicians is in their own way enacting a commentary on the world of politics anyway. To then comment on them just feels like adding another layer. I find it very difficult to do jokes about current politics because for me it's all about... I actually genuinely want people to be involved properly, you know? I mean, the number of people who don't vote... Frightening, really.