A Quote by Jacob T. Schwartz

Because of mathematics precise, formal character, mathematical arguments remain sound even when they are long and complex. In contast, common sense arguments can generally be trusted only if they remain short; even moderately long nonmathematical arguments rapidly becomes farfetched an dubious.

Related Quotes

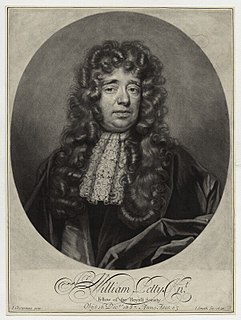

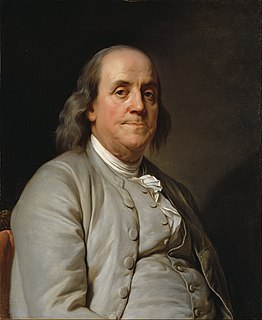

The method I take to do this is not yet very usual; for instead of using only comparative and superlative Words, and intellectual Arguments, I have taken the course (as a Specimen of the Political Arithmetic I have long aimed at) to express myself in Terms of Number, Weight, or Measure; to use only Arguments of Sense, and to consider only such Causes, as have visible Foundations in Nature.

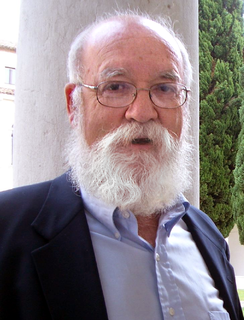

Highly technical philosophical arguments of the sort many philosophers favor are absent here. That is because I have a prior problem to deal with. I have learned that arguments, no matter how watertight, often fall on deaf ears. I am myself the author of arguments that I consider rigorous and unanswerable but that are often not such much rebutted or even dismissed as simply ignored.

As long as we try to project from the relative and conditioned to the absolute and unconditioned, we shall keep the pendulum swinging between dogmatism and skepticism. The only way to stop this increasingly tiresome pendulum swing is to change our conception of what philosophy is good for. But that is not something which will be accomplished by a few neat arguments. It will be accomplished, if it ever is, by a long, slow process of cultural change - that is to say, of change in common sense, changes in the intuitions available for being pumped up by philosophical arguments.

Yes, I share your concern: how to program well -though a teachable topic- is hardly taught. The situation is similar to that in mathematics, where the explicit curriculum is confined to mathematical results; how to do mathematics is something the student must absorb by osmosis, so to speak. One reason for preferring symbol-manipulating, calculating arguments is that their design is much better teachable than the design of verbal/pictorial arguments. Large-scale introduction of courses on such calculational methodology, however, would encounter unsurmoutable political problems.

Some of my understanding of what philosophy and ethics is has changed very slowly. One thing that has changed is this for quite a long time I bought-into the idea that philosophy is basically about arguments. I'm increasingly of the view that it isn't. The most interesting things in philosophy aren't arguments. The thing that I think is underestimated is what I call a form of attending. I think that philosophy is at least as much about carefully attending to things as it is about the structure of arguments.

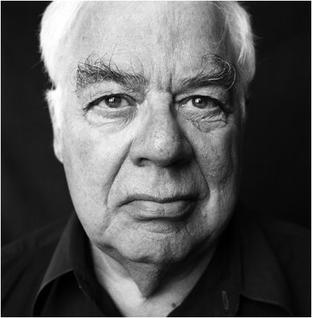

I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech - the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don't convince me and that our civilization over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notice.

When confronted with two courses of action I jot down on a piece of paper all the arguments in favor of each one, then on the opposite side I write the arguments against each one. Then by weighing the arguments pro and con and cancelling them out, one against the other, I take the course indicated by what remains.

Complete knowledge of the nature of an analytic function must also include insight into its behavior for imaginary values of the arguments. Often the latter is indispensable even for a proper appreciation of the behavior of the function for real arguments. It is therefore essential that the original determination of the function concept be broadened to a domain of magnitudes which includes both the real and the imaginary quantities, on an equal footing, under the single designation complex numbers.

Interpretations of Muslim assimilation have gravitated between two arguments: that Muslims will remain as permanent outsiders or that Muslims will blend in with little difficulty at all. Mucahit Bilici demonstrates how wanting these arguments are. Finding Mecca in America takes us into the uncharted territory of what it is actually like to be Muslim immigrants in the United States. I am especially impressed by the study's theoretical depth and empirical insights.

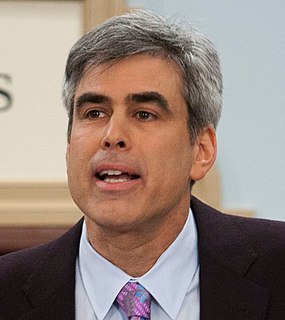

I'm sure Donald Trump will think that he has the truth, and some journalist is arguing that he has truth, and somebody else is arguing that they have the truth. And in fact it's even worse than that because they're so hell bent on their arguments that they will distort the truth consciously. They'll manipulate the facts to support their arguments because they're so hung up in the fight. That's where the problem is, so we argue all the time.