A Quote by James A. Michener

Animals form an inalienable fragment of nature, and if we hasten the disappearance of even one species, we diminish our world and our place in it.

Related Quotes

But that Franklin trip changed me profoundly. As I believe wilderness experience changes everyone. Because it puts us in our place. The human place, which our species inhabited for most of its evolutionary life. That place that shaped our psyches and made us who we are. The place where nature is big and we are small.

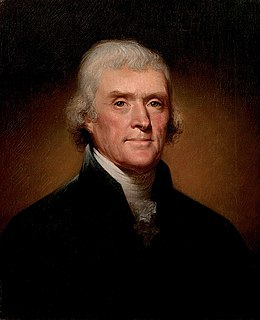

The movements of nature are in a never ending circle. The animal species which has once been put into a train of motion, is still probably moving in that train. For if one link in nature's chain might be lost, another and another might be lost, till this whole system of things should evanish by piece-meal; a conclusion not warranted by the local disappearance of one or two species of animals, and opposed by the thousands and thousands of instances of the renovating power constantly exercised by nature for the reproduction of all her subjects, animal, vegetable, and mineral.

There is today a frightful disappearance of living species, be they plants or animals. And it's clear that the density of human beings has become so great, if I can say so, that they have begun to poison themselves. And the world in which I am finishing my existence is no longer a world that I like.

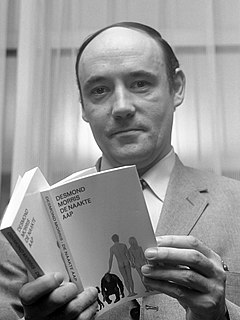

It must be stressed that there is nothing insulting about looking at people as animals. We are animals, after all. Homo sapiens is a species of primate, a biological phenomenon dominated by biological rules, like any other species. Human nature is no more than one particular kind of animal nature. Agreed, the human species is an extraordinary animal; but all other species are also extraordinary animals, each in their own way, and the scientific man-watcher can bring many fresh insights to the study of human affairs if he can retain this basic attitude of evolutionary humility.

Yet the experience of four thousand years should enlarge our hopes, and diminish our apprehensions: we cannot determine to what height the human species may aspire in their advances towards perfection; but it may safely be presumed, that no people, unless the face of nature is changed, will relapse into their original barbarism.

Human beings are not inevitable, and our brief existence is not preordained to be extended into the distant future. If Homo sapiens is to have a continued presence on earth, humankind will reevaluate its sense of place in the world and modify its strong species-centric stewardship of the planet. Our collective concepts of morality and ethics have a direct impact on our species' ultimate fate.

Many things that human words have upset are set at rest again by the

silence of animals. Animals move through the world like a caravan of

silence. A whole world, that of nature and that of animals, is filled

with silence. Nature and animals seem like protuberances of silence.

The silence of animals and the silence of nature would not be so great

and noble if it were merely a failure of language to materialize.

Silence has been entrusted to the animals and to nature as something

created for its own sake.

Our beliefs about ourselves in relation to the world around us are the roots of our values, and our values determine not only our immediate actions, but also, over the course of time, the form of our society. Our beliefs are increasingly determined by science. Hence it is at least conceivable that what science has been telling us for three hundred years about man and his place in nature could be playing by now an important role in our lives.

But the nature of our civilized minds is so detached from the senses, even in the vulgar, by abstractions corresponding to all theabstract terms our languages abound in, and so refined by the art of writing, and as it were spiritualized by the use of numbers, because even the vulgar know how to count and reckon, that it is naturally beyond our power to form the vast image of this mistress called "Sympathetic Nature.

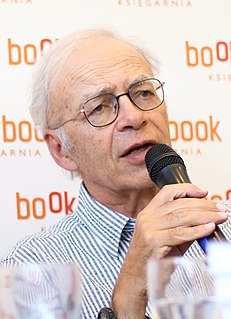

My aim is to advocate that we make this mental switch in respect of our attitudes and practices towards a very large group of beings: members of species other than our own - or, as we popularly though misleadingly call them, animals. In other words, I am urging that we extend to other species the basic principle of equality that most of us recognize should be extended to all members of our own species.

Humans, like all other creatures, must make a difference; otherwise, they cannot live. But unlike other creatures, humans must make a choice as to the kind and scale of difference they make. If they choose to make too small a difference, they diminish their humanity. If they choose to make too great a difference, they diminish nature, and narrow their subsequent choices; ultimately, they diminish or destroy themselves. Nature, then, is not only our source but also our limit and measure.

The ruling British elite are like animals--not only in their morality, but in their outlook on knowledge. They are clever animals, who are masters of the wicked nature of their own species, and recognize ferally the distinctions of the hated human species. Nonetheless, obsessively dedicated to being such animals, they can not [sic] assimilate those qualities unique to true human beings.