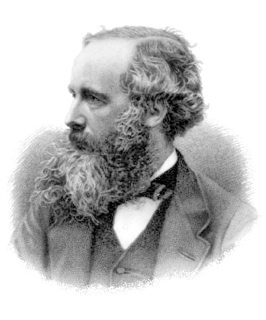

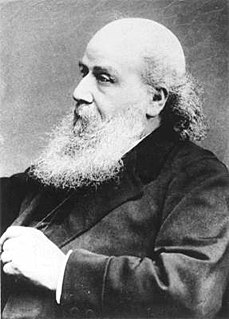

A Quote by James Clerk Maxwell

The true Logic for this world is the Calculus of Probabilities, which takes account of the magnitude of the probability.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

One influential philosophical position about the use of probability in science holds that probabilities are objective only if they are based on micro-physics; all other probabilities should be interpreted subjectively, as merely revealing our ignorance about physical details. I have argued against this position, contending that the objectivity of micro-physical probabilities entails the objectivity of macro-probabilities.

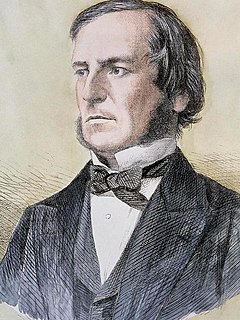

I am now about to set seriously to work upon preparing for the press an account of my theory of Logic and Probabilities which in its present state I look upon as the most valuable if not the only valuable contribution that I have made or am likely to make to Science and the thing by which I would desire if at all to be remembered hereafter.

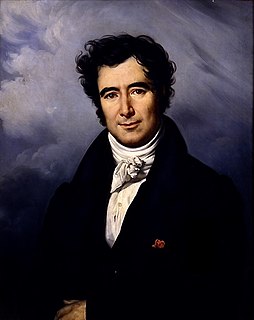

If an event can be produced by a number n of different causes, the probabilities of the existence of these causes, given the event (prises de l'événement), are to each other as the probabilities of the event, given the causes: and the probability of each cause is equal to the probability of the event, given that cause, divided by the sum of all the probabilities of the event, given each of the causes.

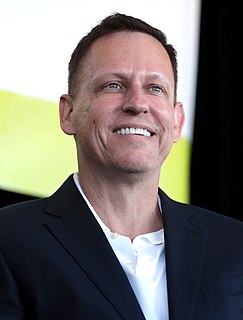

But the indeterminate future is somehow one in which probability and statistics are the dominant modality for making sense of the world. Bell curves and random walks define what the future is going to look like. The standard pedagogical argument is that high schools should get rid of calculus and replace it with statistics, which is really important and actually useful. There has been a powerful shift toward the idea that statistical ways of thinking are going to drive the future.

Without doubt, matter is unlimited in extent, and, in this sense, infinite; and the forces of Nature mould it into an innumerable number of worlds. Would it be at all astonishing if, from the universal dice-box, out of an innumberable number of throws, there should be thrown out one world infinitely perfect? Nay, does not the calculus of probabilities prove to us that one such world out of an infinite number, must be produced of necessity?