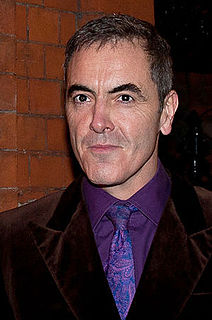

A Quote by James Nesbitt

We have to get behind the scientists and push for a dementia breakthrough. It could be that we fear dementia out of a sense of hopelessness, but there is hope, and it rests in the hands of our scientists.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

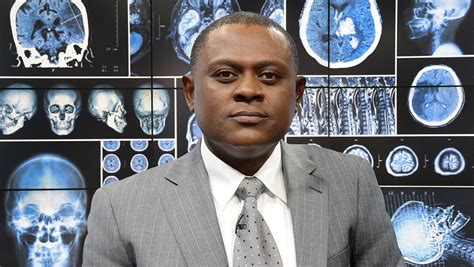

I've had five grandparents who have had Alzheimer's. I've been involved in raising money for two decades, so I thought, how could I combine my work with this commitment to helping dementia? One of the myths is that it's an older person's disease. We're seeing early onset dementia among people at 45. It's the disease of everybody.

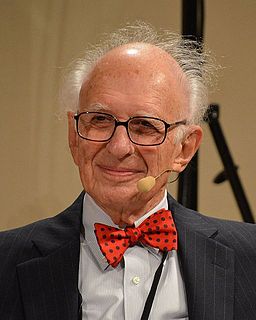

Historians of a generation ago were often shocked by the violence with which scientists rejected the history of their own subject as irrelevant; they could not understand how the members of any academic profession could fail to be intrigued by the study of their own cultural heritage. What these historians did not grasp was that scientists will welcome the history of science only when it has been demonstrated that this discipline can add to our understanding of science itself and thus help to produce, in some sense, better scientists.

My mother was wonderfully out about her dementia. She would sort of - she would say to me, I came out to the window cleaner about having dementia. You know, I love the way that verb for coming out of the closet has now become so socially useful for all sorts of situations, like when you need to explain to the window cleaner that you don't know if you paid him or not.

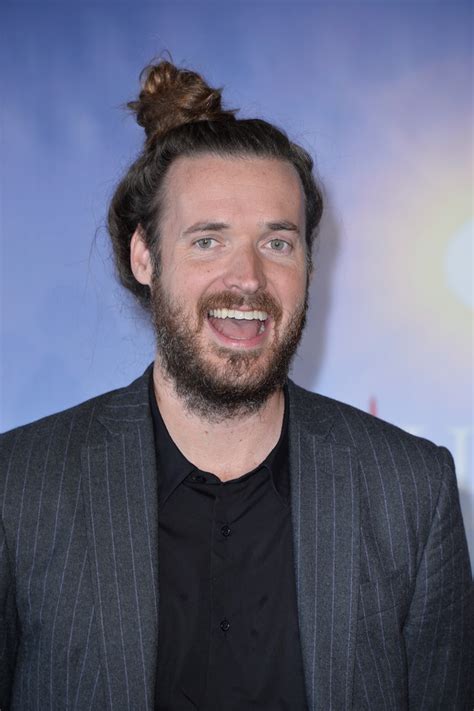

My two older brothers are both molecular biologists and neuroscientists, and I feel like representing them accurately is never done in movies, and I really wanted to at least capture the spirit of a Ph.D. student whose goal and aspiration is to increase the sum total of human knowledge. That is noble. That was really, really important, to capture the three-dimensionality of scientists. Scientists fall in love, scientists have the greatest sense of humor, scientists are passionate.

You got to have an enemy to fight. And when you have an enemy to fight, then you can unite the entire world behind you, and you seize power. That was Hitler's plan. His enemy: the Jew. Al Gore's enemy, the U.N.'s enemy: global warming. Then you get the scientists - eugenics. You get the scientists - global warming. Then you have to discredit the scientists who say, 'That's not right.' And you must silence all dissenting voices. That's what Hitler did.

How did scientists get money in the past? They were either lucky and independently wealthy, like Darwin, or they had patrons, like Galileo. Universities or governments have become patrons only in the last few generations. Many of the great scientists of the past were in debt to their patrons in the same sense that modern scientists are influenced by what their granting agencies want.