A Quote by Jane Austen

When I look out on such a night as this, I feel as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world; and there certainly would be less of both if the sublimity of Nature were more attended to, and people were carried more out of themselves by contemplating such a scene.

Related Quotes

GOOD AS NEW was born out of the idea of writing a play where the stakes were high and the collisions were of a verbal nature. Also I wanted to write a play where people were smarter than I was, and more alive than I feel normally. I became interested in the idea of characters who would surprise me. I guess one could argue that nothing comes out of you that wasn't within you to begin with, but maybe there are ways to trick yourself into becoming more an observer or an advocate for the characters.

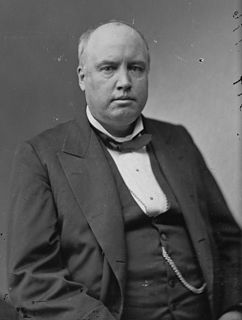

In my judgment, the Deists were all successfully answered. The god of nature is certainly as bad as the God of the Old Testament. It is only when we discard the idea of a deity, the idea of cruelty or goodness in nature, that we are able ever to bear with patience the ills of life. I feel that I am neither a favorite nor a victim. Nature neither loves nor hates me.

My parents were both first-generation Irish Catholics raised in Brooklyn. But it was more for me - it was that women of that generation were even less likely to express themselves, more likely to have that active interior life that they didn't dare speak out. So I was interesting in women of that era. I was interested in the language of that era. There's so much. And, certainly, this is cultural, so much there wasn't spoken about.

Neither capitalism nor socialism is capable of meeting our unprecedented global challenges. Both came out of early industrial times, and we are now well into the post-industrial age. Both came out of times when the West still oriented much more to the domination side of the social scale, so both these theories did not pay attention to caring for people and nature.

After every happiness comes misery; they may be far apart or near. The more advanced the soul, the more quickly does one follow the other. What we want is neither happiness nor misery. Both make us forget our true nature; both are chains-one iron, one gold; behind both is the Atman, who knows neither happiness nor misery. These are states, and states must ever change; but the nature of the Atman is bliss, peace, unchanging. We have not to get it, we have it; only wash away the dross and see it.

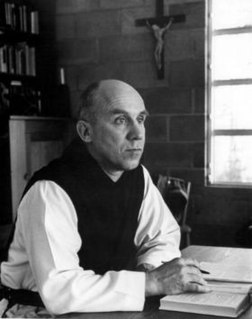

Then it was as if I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depths of their hearts where neither sin nor desire nor self-knowledge can reach, the core of their reality, the person that each one is in God's eyes. If only they could see themselves as they really are. If only we could see each other that way all the time, there would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed . . . I suppose the big problem would be that we would fall down and worship each other.

The dominant orthodoxy in development economics was that Third World countries were trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty that could be broken only by massive foreign aid from the more prosperous industrial nations of the world. This was in keeping with a more general vision on the Left that people were essentially divided into three categories - the heartless, the helpless, and wonderful people like themselves, who would rescue the helpless by playing Lady Bountiful with the taxpayers' money.