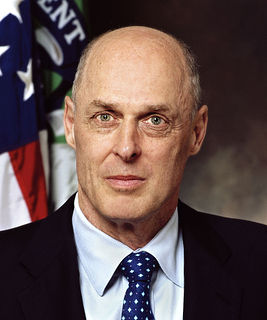

A Quote by Janet Yellen

Although most Americans apparently loathe inflation, Yale economists have argued that a little inflation may be necessary to grease the wheels of the labor market and enable efficiency-enhancing changes in relative pay to occur without requiring nominal wage cuts by workers.

Related Quotes

There is no such thing as agflation. Rising commodity prices, or increases in any prices, do not cause inflation. Inflation is what causes prices to rise. Of course, in market economies, prices for individual goods and services rise and fall based on changes in supply and demand, but it is only through inflation that prices rise in aggregate.

Since it is to the advantage of the wage-payer to pay as little as possible, even well-paid labor will have no more than what is regarded in a particular society as the reasonable level of subsistence. The lower ranks of labor will commonly have less, and if public relief were afforded even up to the wage-level of the lowest ranks of labor, that relief would compete in the labor market; check or dry up the supply of wage-labor. It would tend to render the performance of work by the wage-earner redundant.

I would be uncomfortable raising the federal funds rate if readings on wage growth, core consumer prices, and other indicators of underlying inflation pressures were to weaken, if market-based measures of inflation compensation were to fall appreciably further, or if survey-based measures were to begin to decline noticeably.

Significant changes in the growth rate of money supply, even small ones, impact the financial markets first. Then, they impact changes in the real economy, usually in six to nine months, but in a range of three to 18 months. Usually in about two years in the US, they correlate with changes in the rate of inflation or deflation."

"The leads are long and variable, though the more inflation a society has experienced, history shows, the shorter the time lead will be between a change in money supply growth and the subsequent change in inflation.