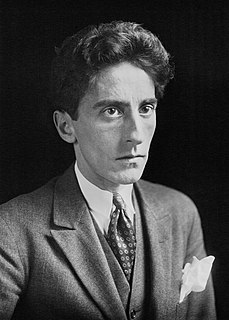

A Quote by Jean Cocteau

How our old friend [Michelangelo] of the Sistine would have loved to photograph his workers, perched on the fragile planks. Dali was right to say Leonardo only worked from photographs.

Related Quotes

A photographer who does not know how to translate his feelings and ideas into a graphically satisfactory form is bound to produce ineffective photographs, no matter how idealistic, compassionate, sensitive or imaginative he may be. For in order to be considered good, a photograph must not only say something worthwhile, it must say it well.

How foolish of me to believe that it would be that easy. I had confused the appearance of trees and automobiles, and people with a reality itself, and believed that a photograph of these appearances to be a photograph of it. It is a melancholy truth that I will never be able to photograph it and can only fail. I am a reflection photographing other reflections within a reflection. To photograph reality is to photograph nothing.

If I had a friend and loved him because of the benefits which this brought me and because of getting my own way, then it would not be my friend that I loved but myself. I should love my friend on account of his own goodness and virtues and account of all that he is in himself. Only if I love my friend in this way do I love him properly.

In a world where the 2 billionth photograph has been uploaded to Flickr, which looks like an Eggleston picture! How do you deal with making photographs with the tens of thousands of photographs being uploaded to Facebook every second, how do you manage that? How do you contribute to that? What's the point?

Leonardo da Vinci had such a playful curiosity. If you read his notebooks, you'll see he's curious about what the tongue of a woodpecker looks like, but also why the sky is blue, or how an emotion forms on somebody's lips. He understood the beauty of everything. I've admired Leonardo my whole life, both as a kid who loved engineering - he was one of the coolest engineers in history - and then as a college student, when I travelled to see his notebooks and paintings.

Saudi Arabia is so conservative. At first there were photographs of women I took that I couldn't publish - of women without their abayas. So I started writing out little anecdotes about things I couldn't photograph and wove it in with a more obscure picture and called it "moments that got away". I realised these worked as well as the photographs by themselves. There are a lot of photographers who feel the story is all in the photographs but I really believe in weaving in complementary words with the pictures.