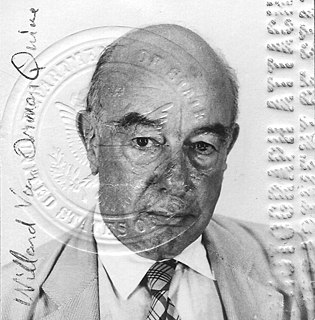

A Quote by Jean-Paul Sartre

That is exactly the writer's problem. What does literature stand for in a hungry world?

Related Quotes

All third world literature is about nation, that identity is the fundamental literary problem in the third world. The writer's identity is insecure because the nation's identity is not secure. The nation doesn't provide the third world writer with a secure identity, because the nation is colonized, it's oppressed, it's part of somebody else's empire.

Christ and the life of Christ is at this moment inspiring the literature of the world as never before, and raising it up a witness against waste and want and war. It may confess Him, as in Tolstoi's work it does, or it may deny Him, but it cannot exclude Him; and in the degree that it ignores His spirit, modern literature is artistically inferior. In other words, all good literature is now Christmas literature.