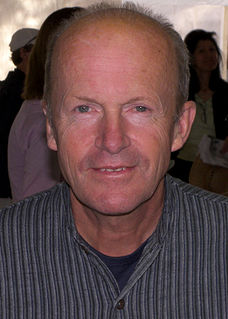

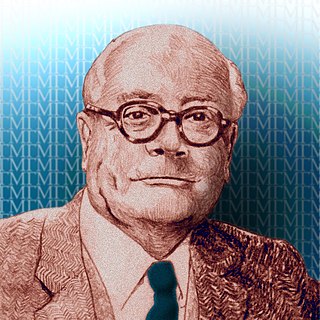

A Quote by Jim Crace

Because I'm a walker, natural history is my subject; I've always been obsessed with landscape, and I have an elegiac tone in most of my books.

Related Quotes

I really only write about inner landscapes and most people don't see them, because they see practically nothing within, because they think that because it's inside, it's dark, and so they don't see anything. I don't think I've ever yet, in any of my books, described a landscape. There's really nothing of the kind in any of them. I only ever write concepts. And so I'm always referring to "mountains" or "a city" or "streets." But as to how they look: I've never produced a description of a landscape. That's never even interested me.

The world is moving into a phase when landscape design may well be recognized as the most comprehensive of the arts. Man creates around him an environment that is a projection into nature of his abstract ideas. It is only in the present century that the collective landscape has emerged as a social necessity. We are promoting a landscape art on a scale never conceived of in history.

I have long been interested in landscape history, and when younger and more robust I used to do much tramping of the English landscape in search of ancient field systems, drove roads, indications of prehistoric settlement. Towns and cities, too, which always retain the ghost of their earlier incarnations beneath today's concrete and glass.

Americans, more than most people, believe that history is the result of individual decisions to implement conscious intentions. For Americans, more than most people, history has been that.... This sense of openness, of possibility and autonomy, has been a national asset as precious as the topsoil of the Middle West. But like topsoil, it is subject to erosion; it requires tending. And it is not bad for Americans to come to terms with the fact that for them too, history is a story of inertia and the unforeseen.

When I was doing mainly music, I used to stick a microphone out the window, into the countryside, and create a live mix. I wanted to put air in electronic music. I record the sounds of twigs, barks, and stones. I've always been obsessed with the idea of combining the natural and the man-made. It's not because I think the technology is crap, or that I'm trying to work against it, but that juxtaposition is truly beautiful. The question of what is natural and unnatural is very open.

Writing of history is our only heuristic principle. The Germans have a word for it, einfühlen. It is the ability to experience the past in the present and to recreate it. In my books, I have tried to recreate it in the most natural way possible: History must be integrated into the story without the weight of premonition.