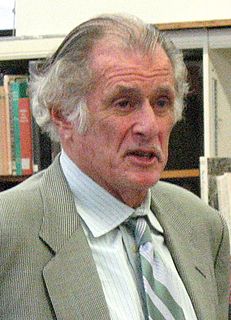

A Quote by Jim McKay

I was the first voice of Baltimore television in 1947.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

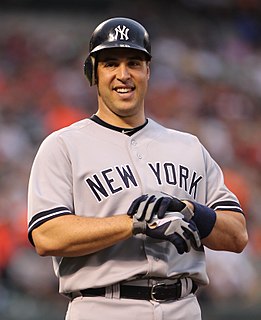

My first few years as TV critic, I would go to parties and people (usually older Posties or ex-Posties who seemed to pride themselves on not watching very much television) would take me by the arm and insist that I watch this show they'd recently starting watching on DVD, about drug dealers in Baltimore.

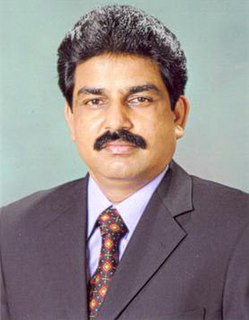

First of all, let me give my comments on the blasphemy law. This law was introduced by the military dictator General Ziaul Haq. No one demanded the blasphemy law in Pakistan. But he wanted to give protection to his undemocratic rule, dictatorship, by using religion. So Pakistan came into being in 1947, and from 1947 until 1986 no case against any minorities was registered under the protection of the blasphemy law. Nobody from minorities was killed and no act of violence happened [against them].