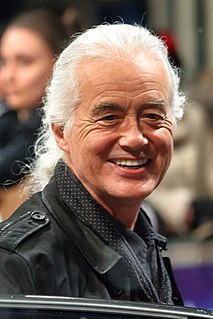

A Quote by Jimmy Page

Certainly, as a guitarist, I was aware of descending chromatic lines and arpeggios long before 1968.

Related Quotes

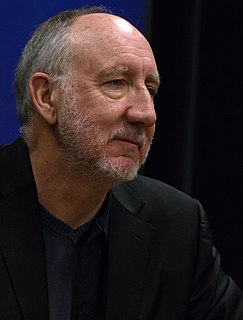

For an electric guitarist to solo effectively on an acoustic guitar you need to develop tricks to avoid the expectation of sustain that comes from playing electrics. Try cascades, for example. Drop arpeggios over open strings, and let the open strings sing as you pick with your fingers. It's kind of a country style of playing, but it works very well in-between heavily strummed parts and fingered lead lines.

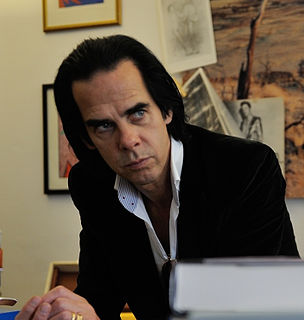

As soon as I start to write I'm very aware, I'm trying to be aware that a reader just might well pick up this poem, a stranger. So when I'm writing - and I think that this is important for all writers - I'm trying to be a writer and a reader back and forth. I write two lines or three lines. I will immediately stop and turn into a reader instead of a writer, and I'll read those lines as if I had never seen them before and as if I had never written them.

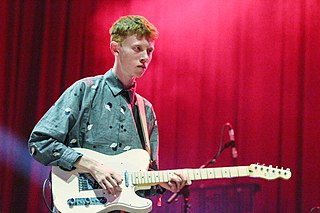

Before Dream Theater took off I used to teach a lot, and one of the things my students often asked me was how to apply the chromatic scale to practical playing situations. You see, their other teachers would give them chromatic warm-up exercises without providing any explanation of how important and versatile this scale actually is.

I didn't know Michael Heizer until I was preparing for my "Earthworks" show in 1968, and somebody called and told me to look at his work. Heizer had already made land art before any of the others and was deeply into it. But he was very young and working out West, so I wasn't aware of his work until he came and showed it to me.