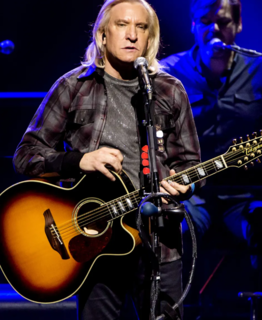

A Quote by Joe Walsh

A homeless veteran should not have to stand at a freeway exit with a cardboard sign. That's not okay.

Related Quotes

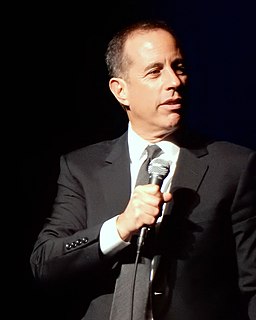

Why is commitment such a big problem for a man? I think that for some reason when a man is driving down that freeway of love, the woman he's with is like an exit, but he doesn't want to get off there. He wants to keep driving. And the woman is like, "Look, gas, food, lodging, that's our exit, that's everything we need to be happy... Get off here, now!" But the man is focusing on the sign underneath that says, "Next exit 27 miles," and he thinks, "I can make it."

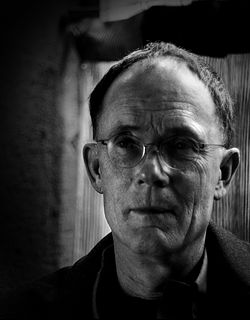

I think that one of the visions that is closest to reality is the cardboard city in the subway station in Tokyo, which is based very closely on a series of documentary photographs of people living like that and of the contents of the boxes. Those are quite haunting because Tokyo homeless people reiterate the whole nature of living in Tokyo in these cardboard boxes, they're only slightly smaller than Tokyo apartments, and they have almost as many consumer goods. It's a nightmare of boxes within boxes.

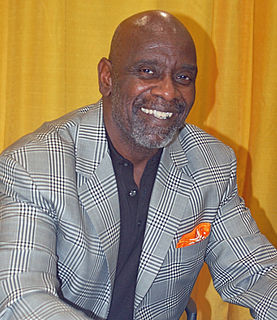

The freeway experience ... is the only secular communion Los Angeles has. Mere driving on the freeway is in no way the same as participating in it. Anyone can "drive" on the freeway, and many people with no vocation for it do, hesitating here and resisting there, losing the rhythm of the lane change, thinking about where they came from and where they are going. Actual participation requires total surrender, a concentration so intense as to seem a kind of narcosis, a rapture-of-the-freeway. The mind goes clean. The rhythm takes over.

I removed the freeway from its temporal context. Overpasses, cloverleafs, exit ramps took on the personality of Mayan ruins for me. Without destination, without cessation, my run was often silent and empty; there were no increments, no arbitrary graduations reducing time to functional units. I abstracted and purified.