A Quote by Johannes Vilhelm Jensen

Whenever one reads of the determination of the species, or opens a book on natural science and history, in whatever language, one inevitably comes across the name of Linne.

Related Quotes

The scientific observer of the realm of nature is in a sense naturally and inevitably disinterested. At least, nothing in the natural scene can arouse his bias. Furthermore, he stands completely outside of the natural so that his mind, whatever his limitations, approximates pure mind. The observer of the realm of history cannot be disinterested in the same way, for two reasons: first, he must look at history from some locus in history; secondly, he is to a certain degree engaged in its ideological conflicts.

Biology is a science of three dimensions. The first is the study of each species across all levels of biological organization, molecule to cell to organism to population to ecosystem. The second dimension is the diversity of all species in the biosphere. The third dimension is the history of each species in turn, comprising both its genetic evolution and the environmental change that drove the evolution. Biology, by growing in all three dimensions, is progressing toward unification and will continue to do so.

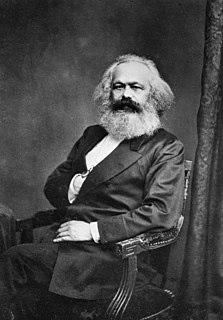

Darwin's book is very important and serves me as a basis in natural science for the class struggle in history. One has to put up with the crude English method of development, of course. Despite all deficiencies not only is the death-blow dealt here for the first time to 'teleology' in the natural sciences, but their rational meaning is empirically explained.

One dictionary that I consulted remarks that "natural history" now commonly means the study of animals and plants "in a popular and superficial way," meaning popular and superficial to be equally damning adjectives. This is related to the current tendency in the biological sciences to label every subdivision of science with a name derived from the Greek. "Ecology" is erudite and profound; while "natural history" is popular and superficial. Though, as far as I can see, both labels apply to just about the same package of goods.

In fact, for a period stretching over seven hundred years, the international language of science was Arabic. For this was the language of the Qur'an, the holy book of Islam, and thus the official language of the vast Islamic Empire that, by the early eighth century CE, stretched from India to Spain.

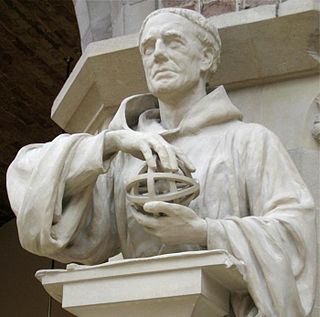

But we must here state that we should not see anything if there were a vacuum. But this would not be due to some nature hindering species, and resisting it, but because of the lack of a nature suitable for the multiplication of species; for species is a natural thing, and therefore needs a natural medium; but in a vacuum nature does not exist.

I am particularly fond of [Emmanuel Mendes da Costa's] Natural History of Fossils because this treatise, more than any other work written in English, records a short episode expressing one of the grand false starts in the history of natural science and nothing can be quite so informative and instructive as a juicy mistake.