A Quote by John Crowe Ransom

Their free verse was no form at all, yet it made history.

Related Quotes

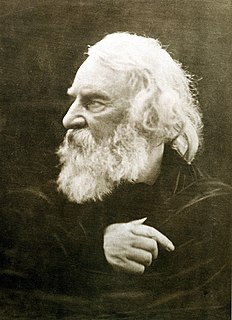

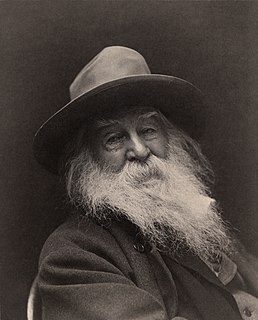

I compelled myself all through to write an exercise in verse, in a different form, every day of the year. I turned out my page every day, of some sort - I mean I didn't give a damn about the meaning, I just wanted to master the form - all the way from free verse, Walt Whitman, to the most elaborate of villanelles and ballad forms. Very good training. I've always told everybody who has ever come to me that I thought that was the first thing to do.

I know that one of the things that I really did to push myself was to write more formal poems, so I could feel like I was more of a master of language than I had been before. That was challenging and gratifying in so many ways. Then with these new poems, I've gone back to free verse, because it would be easy to paint myself into a corner with form. I saw myself becoming more opaque with the formal poems than I wanted to be. It took me a long time to work back into free verse again. That was a challenge in itself. You're always having to push yourself.

Verse in itself does not constitute poetry. Verse is only an elegant vestment for a beautiful form. Poetry can express itself in prose, but it does so more perfectly under the grace and majesty of verse. It is poetry of soul that inspires noble sentiments and noble actions as well as noble writings.