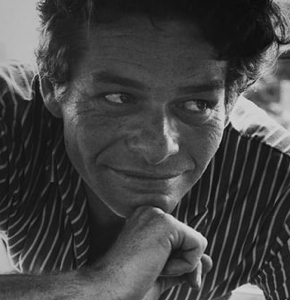

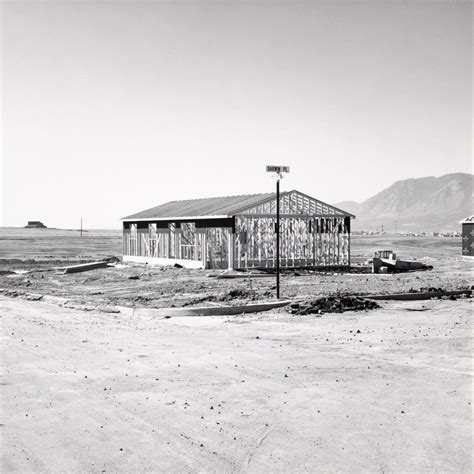

A Quote by John Pfahl

It is not without trepidation that I have appropriated the codes of the Sublime and the Picturesque in my work. After all, serious photographers have spent most of this century trying to expunge such extravagances from their art. The tradition lives on, mostly in calendars and picture postcards. I was challenged to rework and revitalize that which had been so roundly denigrated.

Related Quotes

It is that faculty by which we discover and enjoy the beautiful, the picturesque, and the sublime in literature, art, and nature; which recognizes a noble thought, as a virtuous mind welcomes a pure sentiment by a involuntary glow of satisfaction. But while the principle of perception is inherent in the soul, it requires a certain amount of knowledge to draw out and direct it.

I definitely enjoy liturgical work and choral work from the 15th century and 16th century, but I play in churches with a bit of trepidation, and it's not something I enjoy because there are all these problems. It's an implication that you're part of the theological apparatus, like for atheists or something, and I don't like that. I like playing with the form, inhabiting the tropes of religious music without that promise of angels at the end. It can be awkward, you know?

In the 20th century, we had a century where at the beginning of the century, most of the world was agricultural and industry was very primitive. At the end of that century, we had men in orbit, we had been to the moon, we had people with cell phones and colour televisions and the Internet and amazing medical technology of all kinds.

[on the screenplay for "When Harry Met Sally"] It struck me that the movies had spent more than half a century saying, "They lived happily ever after" and the following quarter century warning that they'll be lucky to make it through the weekend. Possibly now we are now entering a third era in which the movies will be sounding a note of cautious optimism: You know, it just might work.

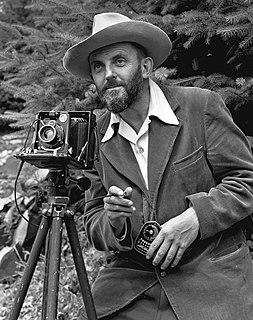

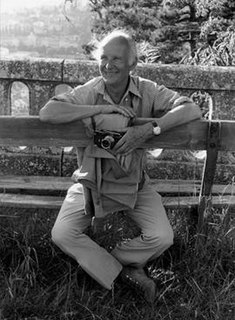

If there is a single factor which separates the best photographers from the wannabes it is the quantity of images which they produce. They seem to be forever shooting. I have watched many of them as they take picture after picture even when they are not photographing. [...] Often these intimate images do not look as though they were taken by the same photographer. And that is their fascination and charm.

My work is based on a tradition quite distinct from the Eckersberg tradition, a Nordic line of development that had never been clearly and consistently defined in the literature on art. This line is not a straight one; it has the strangest and most fascinating twists and curves, and includes such artists as Edvard Munch, Ernest Josephson, Hill, Hansen Jacobsen, Johannes Holbek, Jens Lund, and Emile Nolde. Not all of them equally well known.

After readinf some essay on the nature of human fallibility, I was very aware that we are the recipients of a huge amount of discovery over the last century. Medicine exemplifies this. And that has transitioned us from a world in which people's lives were mostly governed by ignorance to one that's constrained by ineptitude. A century ago, we didn't know, for instance, what diseases afflicted us, what their nature really was, or what to do about them. And that has changed.

Creativity builds upon the public domain. The battle that we're fighting now is about whether the public domain will continue to be fed by creative works after their copyright expires. That has been our tradition but that tradition has been perverted in the last generation. We're trying to use the Constitution to reestablish what has always been taken for granted--that the public domain would grow each year with new creative work.

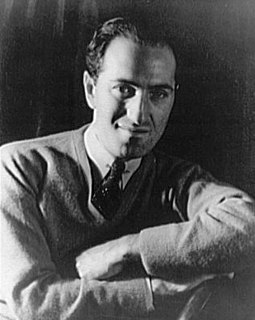

Gershwin's melodic gift was phenomenal. His songs contain the essence of New York in the 1920s and have deservedly become classics of their kind, part of the 20th-century folk-song tradition in the sense that they are popular music which has been spread by oral tradition (for many must have sung a Gershwin song without having any idea who wrote it).