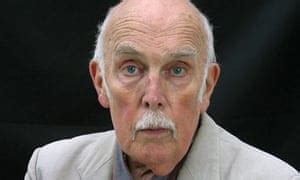

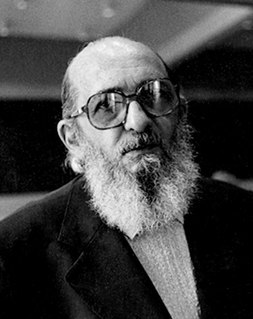

A Quote by John Rawls

Any comprehensive doctrine, religious or secular, can be introduced into any political argument at any time, but I argue that people who do this should also present what they believe are public reasons for their argument. So their opinion is no longer just that of one particular party, but an opinion that all members of a society might reasonably agree to, not necessarily that they would agree to. What's important is that people give the kinds of reasons that can be understood and appraised apart from their particular comprehensive doctrines.

Related Quotes

What's important is that people give the kinds of reasons that can be understood and appraised apart from their particular comprehensive doctrines: for example, that they argue against physician-assisted suicide not just by speculating about God's wrath or the afterlife, but by talking about what they see as assisted suicide's potential injustices.

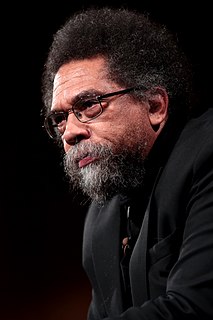

There are two kinds of comprehensive doctrines, religious and secular. Those of religious faith will say I give a veiled argument for secularism, and the latter will say I give a veiled argument for religion. I deny both. Each side presumes the basic ideas of constitutional democracy, so my suggestion is that we can make our political arguments in terms of public reason. Then we stand on common ground. That's how we can understand each other and cooperate.

Now the good of political life is a great political good. It is not a secular good specified by a comprehensive doctrine like those of Kant or Mill. You could characterize this political good as the good of free and equal citizens recognizing the duty of civility to one another: the duty to give citizens public reasons for one's political actions.

Any momentary triumph you think you have gained through argument is really a Pyrrhic victory. The resentment and ill will you stir up is stronger and lasts longer than any momentary change of opinion. It is much more powerful to get others to agree with you through your actions, without saying a word. Demonstrate, do not explicate.

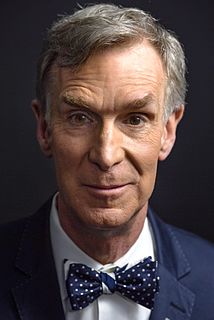

The usefulness of religion - the fact that it gives life meaning, that it makes people feel good - is not an argument for the truth of any religious doctrine. It's not an argument that it's reasonable to believe that Jesus really was born of a virgin or that the Bible is the perfect word of the creator of the universe.

A comprehensive doctrine, either religious or secular, aspires to cover all of life. I mean, if it's a religious doctrine, it talks about our relation to God and the universe; it has an ordering of all the virtues, not only political virtues but moral virtues as well, including the virtues of private life, and the rest. Now we may feel philosophically that it doesn't really cover everything, but it aims to cover everything, and a secular doctrine does also.

Pascal makes no attempt in this most famous argument to show that his Roman Catholicism is true or probably true. The reasons which he suggests for making the recommended bet on his particular faith are reasons in the sense of motives rather than reasons in the sense of grounds. Conceding, if only for the sake of the present argument, that we can have no knowledge here, Pascal tries to justify as prudent a policy of systematic self-persuasion, rather than to provide grounds for thinking that the beliefs recommended are actually true.

I think polling is the best way of gauging public opinion - doing something that's independent, that's quantitative, that doesn't give just the loud voices about how things are going; or doesn't give so called experts the notion that they know what public opinion is. I think that's what makes public opinion polling pretty important. Qualitative assessments of public opinion; going out and talking to people and understanding the nuance to what's behind the numbers. I think it's awfully important as well.

I think polling is important because it gives a voice to the people. It gives a quantitative, independent assessment of what the public feels as opposed to what experts or pundits think the public feels. So often it provides a quick corrective on what's thought to be the conventional wisdom about public opinion. There are any number of examples that I could give you about how wrong the experts are here in Washington, in New York and elsewhere about public opinion that are revealed by public opinion polls.

I like it when people are opinionated. I like an opinion. I like people that will fight for their opinion 'til an argument and through an argument. When they believe in something, they fight for it. I like those people that are perhaps sometimes too full of life - perhaps it's very difficult to be around them; they're not easy going. But I like being around people like that.