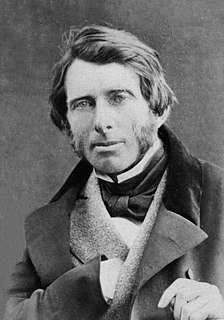

A Quote by John Ruskin

No girl who is well bred, 'kind, and modest, is ever offensively plain; all real deformity means want of manners, or of heart.

Related Quotes

We lived in a very modest house. My father drove modest cars, we didn't travel, we didn't do any of the things that, were commensurate with the kind of income that he was making. So we got this kind of, double message, which was, y'know, "You work hard and you make as much money as you possibly can, but you don't spend any money." And you see how well I learned that lesson.

The delicious faces of children, the beauty of school-girls, "the sweet seriousness of sixteen," the lofty air of well-born, well-bred boys, the passionate histories in the looks and manners of youth and early manhood, and the varied power in all that well-known company that escort us through life,--we know how these forms thrill, paralyze, provoke, inspire, and enlarge us.

And while you and the rest of your kind are battling together-year after year-for this special privilege of being 'bored to death,' the 'real girl' that you're asking about, the marvelous girl, the girl with the big, beautiful, unspoken thoughts in her head, the girl with the big, brave, undone deeds in her heart, the girl that stories are made of, the girl whom you call 'improbable'-is moping off alone in some dark, cold corner-or sitting forlornly partnerless against the bleak wall of the ballroom-or hiding shyly up in the dressing-room-waiting to be discovered!