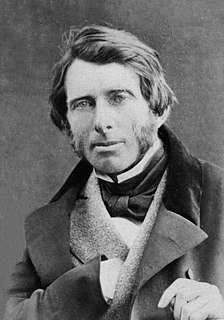

A Quote by John Ruskin

The work of science is to substitute facts for appearances, and demonstrations for impressions.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

The impossibility of separating the nomenclature of a science from the science itself, is owing to this, that every branch of physical science must consist of three things; the series of facts which are the objects of the science, the ideas which represent these facts, and the words by which these ideas are expressed. Like three impressions of the same seal, the word ought to produce the idea, and the idea to be a picture of the fact.

Appearances are not reality; but they often can be a convincing alternative to it. You can control appearances most of the time, but facts are what they are. When the facts are too sharp, you can craft a cheerful version of the situation and cover the facts the way that you can covered a battered old four-slice toaster with a knitted cozy featuring images of kittens.

'Facts, facts, facts,' cries the scientist if he wants to emphasize the necessity of a firm foundation for science. What is a fact? A fact is a thought that is true. But the scientist will surely not recognize something which depends on men's varying states of mind to be the firm foundation of science.

In man's life, the absence of an essential component usually leads to the adoption of a substitute. The substitute is usually embraced with vehemence and extremism, for we have to convince ourselves that what we took as second choice is the best there ever was. Thus blind faith is to a considerable extent a substitute for the lost faith in ourselves; insatiable desire a substitute for hope; accumulation a substitute for growth; fervent hustling a substitute for purposeful action; and pride a substitute for an unattainable self-respect.

It surely can be no offence to state, that the progress of science has led to new views, and that the consequences that can be deduced from the knowledge of a hundred facts may be very different from those deducible from five. It is also possible that the facts first known may be the exceptions to a rule and not the rule itself, and generalisations from these first-known facts, though useful at the time, may be highly mischievous, and impede the progress of the science if retained when it has made some advance.