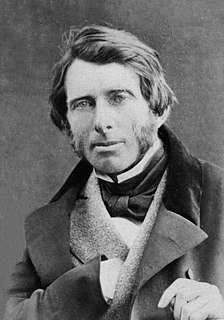

A Quote by John Ruskin

No person who is well bred, kind and modest is ever offensively plain; all real deformity means want for manners or of heart.

Related Quotes

Nor do we accept, as genuine the person not characterized by this blushing bashfulness, this youthfulness of heart, this sensibility to the sentiment of suavity and self-respect. Modesty is bred of self-reverence. Fine manners are the mantle of fair minds. None are truly great without this ornament.

We lived in a very modest house. My father drove modest cars, we didn't travel, we didn't do any of the things that, were commensurate with the kind of income that he was making. So we got this kind of, double message, which was, y'know, "You work hard and you make as much money as you possibly can, but you don't spend any money." And you see how well I learned that lesson.

The delicious faces of children, the beauty of school-girls, "the sweet seriousness of sixteen," the lofty air of well-born, well-bred boys, the passionate histories in the looks and manners of youth and early manhood, and the varied power in all that well-known company that escort us through life,--we know how these forms thrill, paralyze, provoke, inspire, and enlarge us.

What my children appear to be on the surface is no matter to me. I am fooled neither by gracious manners nor by bad manners. I am interested in what is truly beneath each kind of manners...I want my children to be people- each one separate- each one special- each one a pleasant and exciting variation of all the others