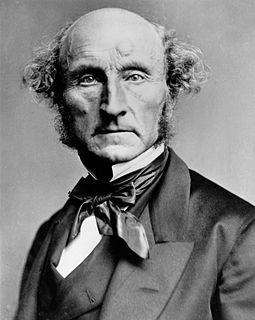

A Quote by John Stuart Mill

Every opinion which embodies somewhat of the portion of truth which the common opinion omits, ought to be considered precious, with whatever amount of error and confusion that truth may be blended.

Related Quotes

We have hitherto considered only two possibilities: that the received opinion may be false, and some other opinion, consequently, true; or that, the received opinion being true, a conflict with the opposite error is essential to a clear apprehension and deep feeling of its truth. But there is a commoner case than either of these; when the conflicting doctrines, instead of being one true and the other false, share the truth between them.

The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

In truth, opinion may be taken for understanding; understanding cannot be taken for opinion. How so? Surely because opinion may be deceived; understanding cannot be. If it could, it would not be understanding but opinion. For true understanding has not only certain truth, but the knowledge of truth.

'In his celebrated book, 'On Liberty', the English philosopher John Stuart Mill argued that silencing an opinion is "a peculiar evil." If the opinion is right, we are robbed of the "opportunity of exchanging error for truth"; and if it's wrong, we are deprived of a deeper understanding of the truth in its "collision with error." If we know only our own side of the argument, we hardly know even that: it becomes stale, soon learned by rote, untested, a pallid and lifeless truth.'

All the followers of science are fully persuaded that the processes of investigation, if only pushed far enough, will give one certain solution to each question to which they can be applied.... This great law is embodied in the conception of truth and reality. The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real.

Error is a supposition that pleasure and pain, that intelligence, substance, life, are existent in matter. Error is neither Mind nor one of Mind's faculties. Error is the contradiction of Truth. Error is a belief without understanding. Error is unreal because untrue. It is that which stemma to be and is not. If error were true, its truth would be error, and we should have a self-evident absurdity -namely, erroneous truth. Thus we should continue to lose the standard of Truth.

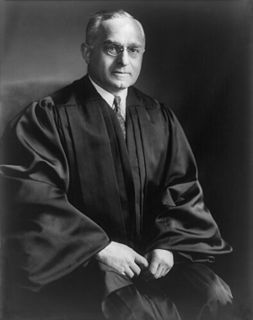

Freedom of expression is the well-spring of our civilization... The history of civilization is in considerable measure the displacement of error which once held sway as official truth by beliefs which in turn have yielded to other truths. Therefore the liberty of man to search for truth ought not to be fettered, no matter what orthodoxies he may challenge.

Then may we not fairly plead in reply that our true lover of knowledge naturally strives for truth, and is not content with common opinion, but soars with undimmed and unwearied passion till he grasps the essential nature of things with the mental faculty fitted to do so, that is, with the faculty which is akin to reality, and which approaches and unites with it, and begets intelligence and truth as children, and is only released from travail when it has thus reached knowledge and true life and satisfaction?

We are always more anxious to be distinguished for a talent which we do not possess, than to be praised for the fifteen which we do possess. Sometimes we are too close to the scene, to see clearly. We "know" ourselves so well that we cannot see how we are perceived by others. Our opinion of ourselves is only "one" opinion and it may not be the truth.

There are two threats to reason, the opinion that one knows the truth about the most important things and the opinion that there is no truth about them. Both of these opinions are fatal to philosophy; the first asserts that the quest for truth is unnecessary, while the second asserts that it is impossible. The Socratic knowledge of ignorance, which I take to be the beginning point of all philosophy, defines the sensible middle ground between two extremes.

The need for truth is not constant; no more than is the need for repose. An idea which is a distortion may have a greater intellectual thrust than the truth; it may better serve the needs of the spirit, which vary. The truth is balance, but the opposite of truth, which is unbalance, may not be a lie.