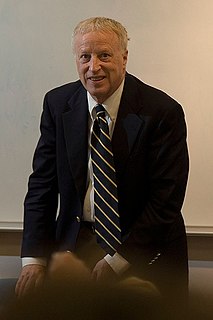

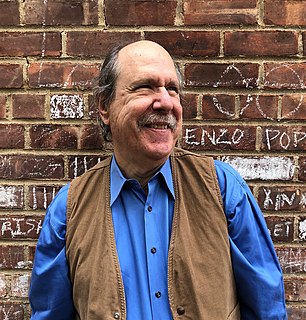

A Quote by John Templeton

I'm really convinced that our descendants a century or two from now will look back at us with the same pity that we have toward the people in the field of science two centuries ago.

Related Quotes

In Britain, journalists often view comparisons with our society going back two, three, or seven centuries as more relevant than comparisons going back two, three, or seven decades. Drunkenness centuries ago is more illuminating than comparative sobriety 30 years ago. The distant past, selectively mined for evidence that justifies our current conduct, becomes more important than living memory.

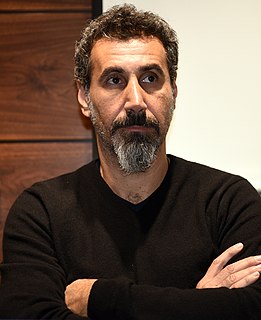

Making two possibilities a reality. Predicting the future of things we all know. Fighting off the diseased programming Of centuries, centuries, centuries, centuries. Science fails to recognise the single most Potent element of human existence. Letting the reigns go to the unfoldings faith, Science has failed our world. Science has failed our mother earth.

I think our children will be living on floating cities, and they will look back on the 20th Century, when people lived in primitive governments founded in previous centuries, and they will be living on modular, sustainable, floating cities that we can't imagine now, that are based on the voluntary choice of citizens. I think we will have a marvellous world in the 21st Century.

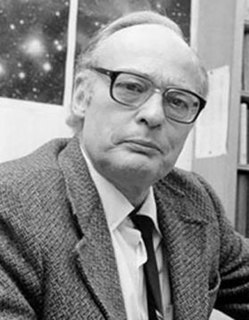

Who of us would not be glad to lift the veil behind which the future lies hidden; to cast a glance at the next advances of

our science and at the secrets of its development during future centuries? What particular goals will there be toward

which the leading mathematical spirits of coming generations will strive? What new methods and new facts in the

wide and rich field of mathematical thought will the new centuries disclose?

Some time ago a little-known Scottish philosopher wrote a book on what makes nations succeed and what makes them fail. The Wealth of Nations is still being read today. With the same perspicacity and with the same broad historical perspective, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have retackled this same question for our own times. Two centuries from now our great-great- . . . -great grandchildren will be, similarly, reading Why Nations Fail.

Human beings of all societies in all periods of history believe that their ideas on the nature of the real world are the most secure, and that their ideas on religion, ethics and justice are the most enlightened. Like us, they think that final knowledge is at last within reach. Like us, they pity the people in earlier ages for not knowing the true facts. Unfailingly, human beings pity their ancestors for being so ignorant and forget that their descendants will pity them for the same reason.

Other centuries had their driving forces. What will ours have been when men look far back to it one day? Maybe it won't be the American Century, after all. Or the Russian Century or the Atomic Century. Wouldn't it be wonderful, Phil, if it turned out to be everybody's century, when people all over the world--free people--found a way to live together? I'd like to be around to see some of that, even the beginning.

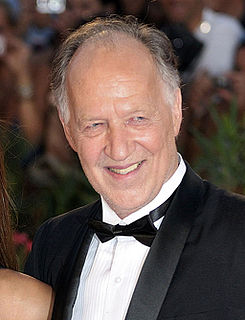

Centuries from now our great-great-great-grandchildren will look back at us with amazement at how we could allow such a precious achievement of human culture as the telling of a story to be shattered into smithereens by commercials, the same amazement we feel today when we look at our ancestors for whom slavery, capital punishment, burning of witches, and the inquisition were acceptable everyday events.

If two or three hundred years from now an earthbound civilization is dying ... and they look back at the opportunity that we have here at the close of the twentieth century to move out into space and they see that we didn't do anything with it ... I don't want history to judge us on having blown this opportunity, and I think history will judge us on this more than on any other issue.

All the research shows that the presence of that phone will do two things to the conversation. It will make the conversation go to trivial matters, and it will decrease the amount of empathy that the two people in the conversation feel toward each other. That phone is a signal that either of us can put our attention elsewhere.

Fellow Americans, our duty is before us tonight. Let us go forward, determined to serve selflessly a vision of man with God, government for people, and humanity at peace. For it is now our task to tend and preserve, through the darkest and coldest nights, that "sacred fire of liberty" that President Washington spoke of two centuries ago, a fire that tonight remains a beacon to all oppressed of the world, shining forth from this kindly, pleasant, greening land we call America.

All this shouldn't last; but it will, always; the human 'always' of course, a century, two centuries... and after that it will be different, but worse. We were the Leopards, the Lions; those who'll take our place will be little jackals, hyenas; and the whole lot of us, Leopards, jackals, and sheep, we'll all go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth.