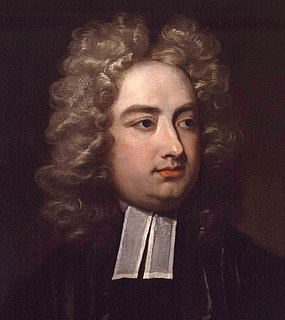

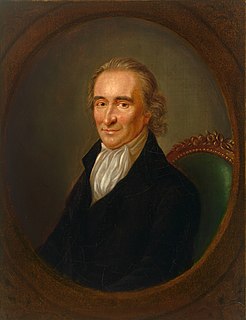

A Quote by Jonathan Swift

That was excellently observed’, say I, when I read a passage in an author, where his opinion agrees with mine. When we differ, there I pronounce him to be mistaken.

Related Quotes

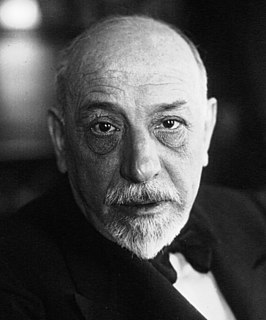

There are three infallible ways of pleasing an author, and the three form a rising scale of compliment: 1, to tell him you have read one of his books; 2, to tell him you have read all of his books; 3, to ask him to let you read the manuscript of his forthcoming book. No. 1 admits you to his respect; No. 2 admits you to his admiration; No. 3 carries you clear into his heart.

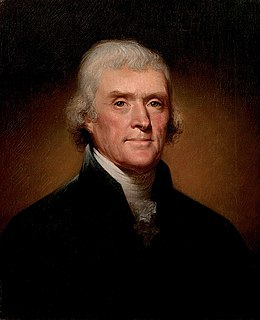

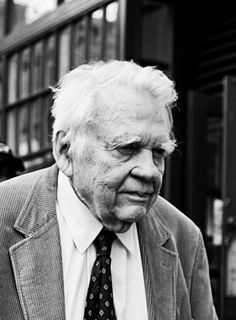

When I hear another express an opinion which is not mine, I say to myself, he has a right to his opinion, as I to mine. Why should I question it? His error does me no injury, and shall I become a Don Quixote, to bring all men by force of argument to one opinion? ...Be a listener only, keep within yourself, and endeavor to establish with yourself the habit of silence, especially in politics.

I need not ask whether I may call on Him or not, for that word 'Whosoever' is a very wide and comprehensive one...My case is urgent, and I do not see how I am to be delivered; but this is no business of mine. He who makes the promise will find ways and means of keeping it. It is mine to obey His commands; it is not mine to direct His counsels. I am His servant, not His solicitor. I call upon Him, and He will deliver.

It has been jestingly said that the works of John Paul Richter are almost unintelligible to any but the Germans, and even to some of them. A worthy German, just before Richter's death, edited a complete edition of his works, in which one particular passage fairly puzzled him. Determined to have it explained at the source, he went to John Paul himself. The author's reply was very characteristic: "My good friend, when I wrote that passage, God and I knew what it meant; it is possible that God knows it still; but as for me, I have totally forgotten."

Lagrange, in one of the later years of his life, imagined that he had overcome the difficulty (of the parallel axiom). He went so far as to write a paper, which he took with him to the Institute, and began to read it. But in the first paragraph something struck him that he had not observed: he muttered: 'Il faut que j'y songe encore', and put the paper in his pocket.' [I must think about it again]