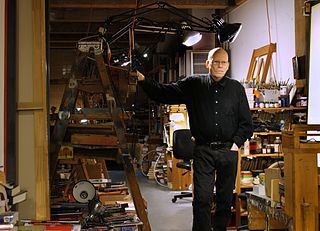

A Quote by Jonathon Keats

To me, the reason to write about [Buckminster] Fuller is because I think that he has ideas that are incredibly pertinent.

Related Quotes

I would have private conversations with [Buckminster Fuller]. I once had an argument, for four hours, about the existence of the Mobius strip. Because he believed in the Klein Bottle, you see. And I said, "How in hell can you claim to believe in the Klein Bottle and think that the Mobius strip is dubious?" He said, "Well, it's a torus." I don't know what he had in his mind as a mathematical background, because I don't think he got topology. Because, in other words, the Mobius strip didn't have angles in it.

Writing a book about [Buckminster Fuller] in the sense of deciding how much to - how much biographically to gloss over and how much I can leave out is relatively easy as it is because the true believers already know everything. They know a lot of things that are not true and they know a lot of things that I thought were (and seems there's very good evidence not to believe) and therefore, my starting point was I think to tell his myth because that's what grabbed me.

Just enough of that to be able to give the reader a sense of skepticism that all - it seemed like all that was necessary. I don't really care. But what I do care about is what was happening within the realm of automobiles at the time that [Buckminster Fuller] invented his Dymaxion car because that is really relevant.

I think that in the first place, why we can get excited about [Buckminster ] Fuller, why it's plausible that people might - why my publisher would publish this book [You belong to the universe] about it long after he's dead and irrelevant by many standards has to do with the fact that he was in a sense coming up with this job for himself that is the job that we now refer to when we speak about world change.