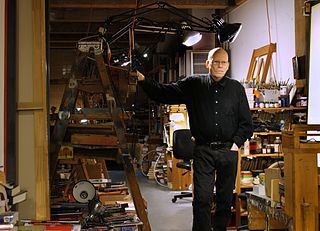

A Quote by Jonathon Keats

I think it was impossible not to come upon a lot of confabulation simply because any good scholarship that has been done since [Buckminster Fuller] death has really delved in that.

Related Quotes

Writing a book about [Buckminster Fuller] in the sense of deciding how much to - how much biographically to gloss over and how much I can leave out is relatively easy as it is because the true believers already know everything. They know a lot of things that are not true and they know a lot of things that I thought were (and seems there's very good evidence not to believe) and therefore, my starting point was I think to tell his myth because that's what grabbed me.

Buckminster Fuller was down in Pennsylvania, then he'd come up and go to his island in Maine. He wanted to remain a New Englander. He taught from '48 to '49 and '50 at Black Mountain College. That's where he met Kenneth Snelson. Fuller kind of stayed a Yankee right in the New England area. So it was pretty easy to get him to come on over, and we would have lectures at the Harvard Science Center.

I didn't grow up with [Buckminster Fuller]. I never met him. I was once close to meeting him as a child at a ski resort one summer. He died in 1983. Only in 1999 or so, 2000, when I was working as an editor at San Francisco Magazine, did I really come back around to that name because Stanford University had just acquired the archive.

Just enough of that to be able to give the reader a sense of skepticism that all - it seemed like all that was necessary. I don't really care. But what I do care about is what was happening within the realm of automobiles at the time that [Buckminster Fuller] invented his Dymaxion car because that is really relevant.