A Quote by Joseph Addison

I am wonderfully pleased when I meet with any passage in an old Greek or Latin author, that is not blown upon, and which I have never met with in any quotation.

Related Quotes

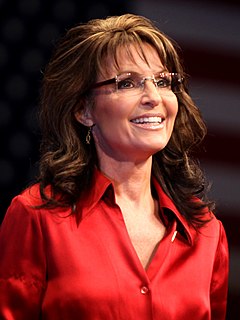

I am dead against art's being self-expression. I see an inherent failure in any story which fails to detach itself from the author-detach itself in the sense that a well-blown soap-bubble detaches itself from the bowl of the blower's pipe and spherically takes off into the air as a new, whole, pure, iridescent world. Whereas the ill-blown bubble, as children know, timidly adheres to the bowl's lip, then either bursts or sinks flatly back again.

The art of quotation requires more delicacy in the practice than those conceive who can see nothing more in a quotation than an extract. Whenever the mind of a writer is saturated with the full inspiration of a great author, a quotation gives completeness to the whole; it seals his feelings with undisputed authority.

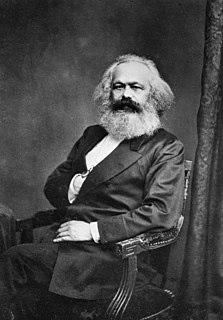

I am not of the opinion generally entertained in this country [England], that man lives by Greek and Latin alone; that is, by knowing a great many words of two dead languages, which nobody living knows perfectly, and which are of no use in the common intercourse of life. Useful knowledge, in my opinion, consists of modern languages, history, and geography; some Latin may be thrown into the bargain, in compliance with custom, and for closet amusement.

The Author of nature has not given laws to the universe, which, like the institutions of men, carry in themselves the elements of their own destruction; he has not permitted in his works any symptom of infancy or of old age, or any sign by which we may estimate either their future or their past duration. He may put an end, as he no doubt gave a beginning, to the present system at some determinate period of time; but we may rest assured, that this great catastrophe will not be brought about by the laws now existing, and that it is not indicated by any thing which we perceive.

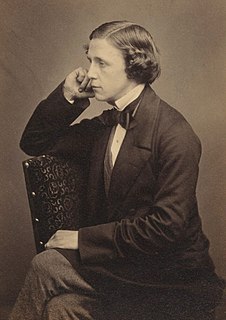

It has been jestingly said that the works of John Paul Richter are almost unintelligible to any but the Germans, and even to some of them. A worthy German, just before Richter's death, edited a complete edition of his works, in which one particular passage fairly puzzled him. Determined to have it explained at the source, he went to John Paul himself. The author's reply was very characteristic: "My good friend, when I wrote that passage, God and I knew what it meant; it is possible that God knows it still; but as for me, I have totally forgotten."