A Quote by Julian Schwinger

Perhaps the most important contribution to science that the Royal Society has made in its three centuries of existence is its early role in publishing Newton's masterful account of his discoveries.

Related Quotes

Charles Darwin [is my personal favorite Fellow of the Royal Society]. I suppose as a physical scientist I ought to have chosen Newton. He would have won hands down in an IQ test, but if you ask who was the most attractive personality then Darwin is the one you'd wish to meet. Newton was solitary and reclusive, even vain and vindictive in his later years when he was president of the society.

Making two possibilities a reality. Predicting the future of things we all know. Fighting off the diseased programming Of centuries, centuries, centuries, centuries. Science fails to recognise the single most Potent element of human existence. Letting the reigns go to the unfoldings faith, Science has failed our world. Science has failed our mother earth.

There is a reward structure in science that is very interesting: Our highest honors go to those who disprove the findings of the most revered among us. So Einstein is revered not just because he made so many fundamental contributions to science, but because he found an imperfection in the fundamental contribution of Isaac Newton.

In the field of Artificial Intelligence there is no more iconic and controversial milestone than the Turing Test, when a computer convinces a sufficient number of interrogators into believing that it is not a machine but rather is a human. It is fitting that such an important landmark has been reached at the Royal Society in London, the home of British Science and the scene of many great advances in human understanding over the centuries. This milestone will go down in history as one of the most exciting.

Lest we forget, the birth of modern physics and cosmology was achieved by Galileo, Kepler and Newton breaking free not from the close confining prison of faith (all three were believing Christians, of one sort or another) but from the enormous burden of the millennial authority of Aristotelian science. The scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was not a revival of Hellenistic science but its final defeat.

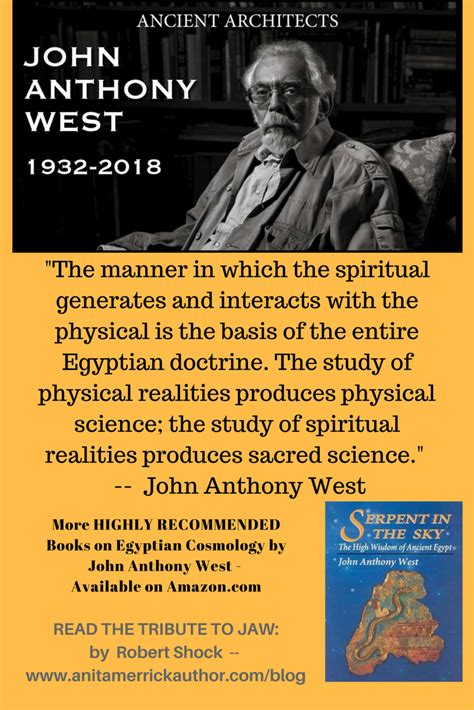

In my view, The Temple of Man is the most important work of scholarship of this century. R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz finally proves the existence of the legendary 'sacred science' of the Ancients and systematically demonstrates its modus operandi. It was this great science-based upon an intimate and exact knowledge of cosmic principles-that fused art, religion, science, and philosophy into one coherent whole and sustained Ancient Egypt for three thousand years.

I am now about to set seriously to work upon preparing for the press an account of my theory of Logic and Probabilities which in its present state I look upon as the most valuable if not the only valuable contribution that I have made or am likely to make to Science and the thing by which I would desire if at all to be remembered hereafter.

Our beliefs about ourselves in relation to the world around us are the roots of our values, and our values determine not only our immediate actions, but also, over the course of time, the form of our society. Our beliefs are increasingly determined by science. Hence it is at least conceivable that what science has been telling us for three hundred years about man and his place in nature could be playing by now an important role in our lives.

Philosophical studies are beset by one peril, a person easily brings himself to think that he thinks; and a smattering of science encourages conceit. He is above his companions. A hieroglyphic is a spell. The gnostic dogma is cuneiform writing to the million. Moreover, the vain man is generally a doubter. It is Newton who sees himself in a child on the sea shore, and his discoveries in the colored shells.

Only when he has published his ideas and findings has the scientist made his contribution, and only when he has thus made it part of the public domain of scholarship can he truly lay claim to it as his own. For his claim resides only in the recognition accorded by peers in the social system of science through reference to his work.