A Quote by Kate Zambreno

With fiction, the works of women are often over-interpreted as autobiography, especially when the main character is a woman, especially if she is seen as privileged.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

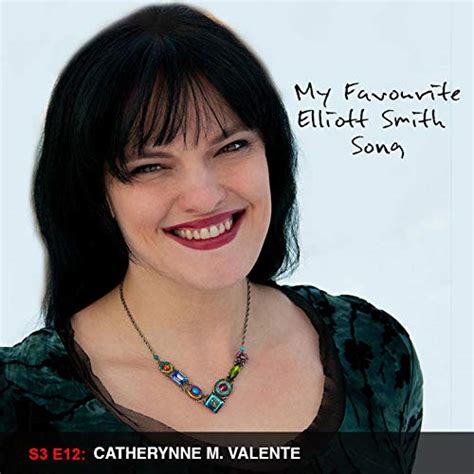

But the thought arrived inside her like a train: Marya Morevna, all in black, here and now, was a point at which all the women she had been met—the Yaichkan and the Leningrader and the chyerti maiden; the girl who saw the birds, and the girl who never did—the woman she was and the woman she might have been and the woman she would always be, forever intersecting and colliding, a thousand birds falling from a thousand oaks, over and over.

Over and over again, stories in women's magazines insist that women can know fulfillment only at the moment of giving birth to a child. They deny the years when she can no longer look forward to giving birth, even if she repeats the act over and over again. In the feminine mystique, there is no other way for a woman to dream of creation or of the future. There is no other way she can even dream about herself, except as her children's mother, her husband's wife.

I'm working on something a little different. It's a technique I call, 'tantric abstinence.' Now, the way this works is I meet a woman, I charm the heck out of her, and then right as she's considering sleeping with me, I say something so awkward that she leaves and I have to start over again with another woman entirely.