A Quote by Kayleigh McEnany

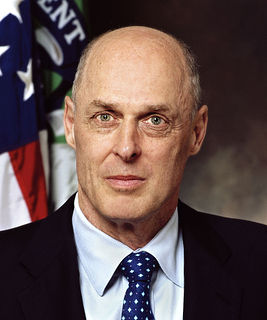

When the President acts, he must do so pursuant to constitutionally enumerated Article II powers or statutory power allocated to him by Congress.

Related Quotes

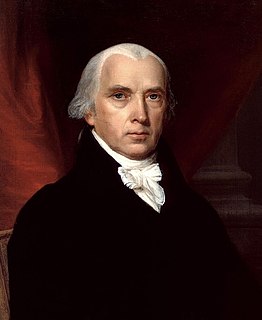

Under Article II, all executive power is vested in one president of the United States. The regulatory state is Congress's efforts to undermine the president's authority. And my hope is we will see a president use that constitutional authority to rein in the uncontrollable, unelected bureaucrats and to rescind regulations.

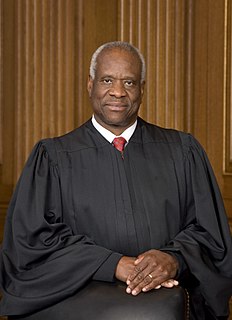

The Court's decision reflects the philosophy that judges should endure whatever interpretive distortions it takes in order to correct a supposed flaw in the statutory machinery. That philosophy ignores the American people's decision to give Congress '[a]ll legislative Powers' enumerated in the Constitution. They made Congress, not this Court, responsible for both making laws and mending them.

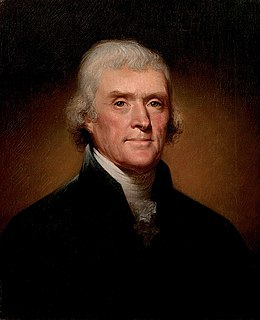

Our tenet ever was . . . that Congress had not unlimited powers to provide for the general welfare, but were restrained to those specifically enumerated; and that, as it was never meant that they should provide for that welfare but by the exercise of the enumerated powers, so it could not have been meant they should raise money for purposes which the enumeration did not place under their action.

Now, therefore, I, Gerald R. Ford, President of the United States, pursuant to the pardon power conferred upon me by Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution, have granted and by these presents do grant a full, free, and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 20, 1969 through August 9, 1974.

Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution, of course, lays out the delegated, enumerated, and therefore limited powers of Congress. Only through a deliberate misreading of the general welfare and commerce clauses of the Constitution has the federal government been allowed to overreach its authority and extend its tendrils into every corner of civil society.

It would reduce the whole instrument to a single phrase, that of instituting a Congress with power to do whatever would be for the good of the United States; and as they would be the sole judges of the good or evil, it would be also a power to do whatever evil they please . . . . Certainly no such universal power was meant to be given them. It [the Constitution] was intended to lace them up straightly within the enumerated powers and those without which, as means, these powers could not be carried into effect.

The Constitution, in addition to delegating certain enumerated powers to Congress, places whole areas outside the reach of Congress' regulatory authority. The First Amendment, for example, is fittingly celebrated for preventing Congress from "prohibiting the free exercise" of religion or "abridging the freedom of speech." The Second Amendment similarly appears to contain an express limitation on the government's authority.