A Quote by Kerry Greenwood

Related Quotes

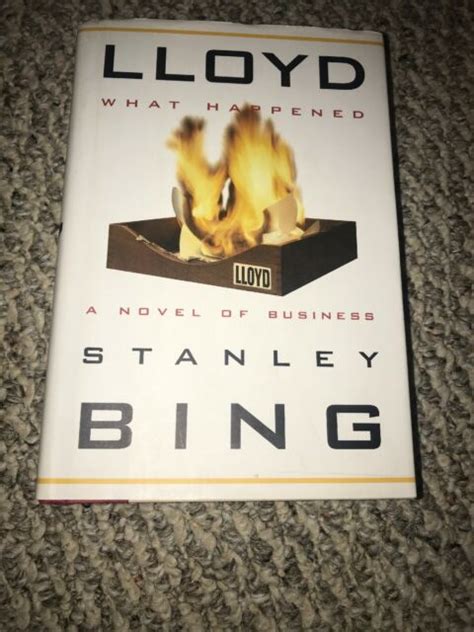

I often use detective elements in my books. I love detective novels. But I also think science fiction and detective stories are very close and friendly genres, which shows in the books by Isaac Asimov, John Brunner, and Glen Cook. However, whilst even a tiny drop of science fiction may harm a detective story, a little detective element benefits science fiction. Such a strange puzzle.

Mma Ramotswe had a detective agency in Africa, at the foot of Kgale Hill. These were its assets: a tiny white van, two desks, two chairs, a telephone, and an old typewriter. Then there was a teapot, in which Mma Ramotswe – the only lady private detective in Botswana – brewed redbush tea. And three mugs – one for herself, one for her secretary, and one for the client. What else does a detective agency really need? Detective agencies rely on human intuition and intelligence, both of which Mma Ramotswe had in abundance. No inventory would ever include those, of course.

I think the detective story is by far the best upholder of the democratic doctrine in literature. I mean, there couldn't have been detective stories until there were democracies, because the very foundation of the detective story is the thesis that if you're guilty you'll get it in the neck and if you're innocent you can't possibly be harmed. No matter who you are.

When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle conceived Sherlock Holmes, why didn't he give the famous consulting detective a few more quirks: a wooden leg, say, and an Oedipus complex? Well, Holmes didn't need many physical tics or personality disorders; the very concept of a consulting detective was still fresh and original in 1887.

The best crime stories are always about the crime and its consequences - you know, 'Crime And Punishment' is the classic. Where you have the crime, and its consequences are the story, but considering the crime and the consequences makes you think about the society in which the crime takes place, if you see what I mean.